Issue No. 4: April, 1997

Publisher’s Notes by Lawrence Tamburri

New Institute Governance Plan by Lawrence Tamburri

The Turning Point by Lawrence Tamburri

Trust by Lawrence Tamburri

Symphony Orchestra Volunteers: Vital Resources by Michael Gehret

An Instrument of Knowledge by Meg Posey and Paul R. Judy

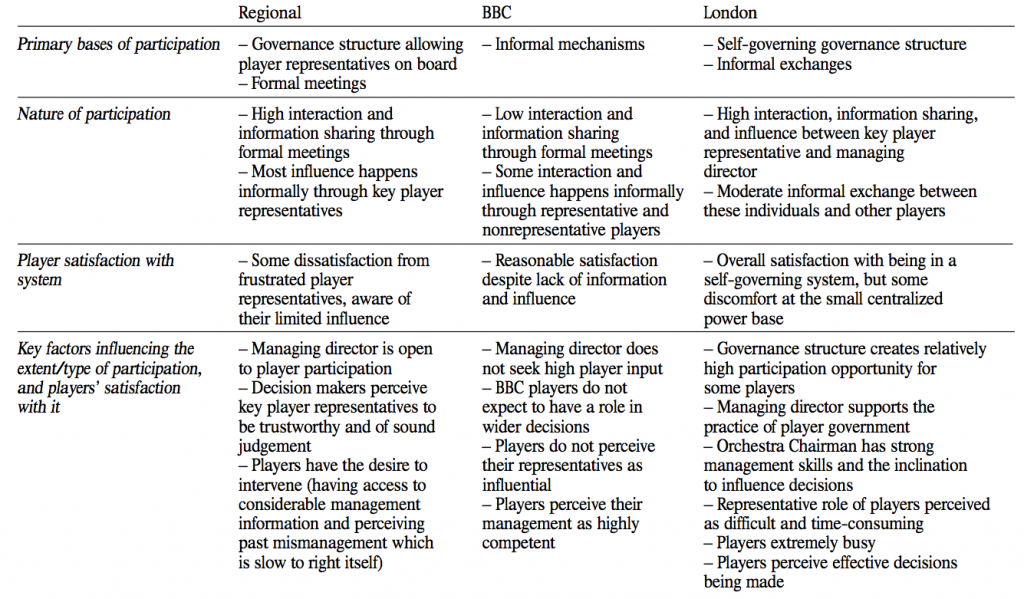

Research Update by Sally Maitlis

Decision Making in British Symphony Orchestras: Formal Structures, Informal Systems, and the Role of Players by Sally Maitlis

Rebuilding the Repertoire for the 21st Century by James Orleans

Toward a Vision of Mutual Responsiveness: Remythologizing the Symphony Orchestra by Marilyn Fischer and Isaiah Jackson

Myths and Magic: A Word from a Conductor by Taavo Virkhaus

About the Cover…by Phillip Huscher

Book Review by Paul R. Judy

Publisher’s Notes

Welcome to the fourth issue of Harmony! We think you will find this issue to be the most thought-provoking yet! But first, a few administrative notes.

As perhaps you observed on the inside front cover, we are restructuring the governance of the Institute. These new arrangements are described in more detail on page viii. And we have moved our office to Evanston, Illinois, where Meg Posey has joined us as administrator. We have also changed our telephone and fax numbers, and e-mail address. Please make a note of these details.

We thank those dedicated people who helped launch the Institute and welcome many new minds and hands to assist with future tasks. These are ongoing steps to build a solid foundation for Institute programs over the longer term.

Moving to the central content of this issue, we continue in our exploration of the unique dynamics of symphony orchestra organizations. A number of the essays will remind readers of the large and, in many cases, untapped human potential which resides in these organizations. More particularly, participants and observers are beginning to suggest how symphony orchestra organizations might change or are, in fact, changing to become better functioning and more effective institutions.

Preceding any “organizational change” process, there is often a turning point at which the leadership from different organizational sectors embraces new ways of thinking and relating, a time when organizational trust begins an upward trend. The New Jersey Symphony Orchestra organization passed through such a point a few years back, and the subsequent transformation provides a good example of the change which is possible in the orchestral workplace. This issue of Harmony opens with a review of this change as expressed by some of the key participants and is followed by some personal thoughts from the NJSO executive director, Larry Tamburri.

In every symphony organization, the orchestra is the central work group; it produces the primary artistic work product. To audiences and community, musicians are the most obvious and necessary participants in an orchestral organization. Operating much more in the background, however, is a cadre of volunteers whose leadership, service, and support are absolutely vital to the success of any American orchestral organization. The significance of these human resources, and the policies and attitudes needed to develop and nourish them, merit broader understanding. We asked Mike Gehret to give Harmony readers an expert’s view on what he aptly describes as the “volunteer-centered” orchestra organization.

As is the case in all nonprofit and for-profit institutions, the board of directors has final legal responsibility for and authority over the affairs of a symphony orchestra organization. The board must ensure that the organization has clear goals and the leadership and resources to achieve them. When board responsibilities are fulfilled poorly, and when the situation is exacerbated by other organizational dysfunction, disaster can result. The demise of the Oakland (California) Symphony Orchestra some 10 years ago provides a case in point. The essay by Meg Posey and Paul Judy, based on an extensively documented history of the Oakland situation, summarizes the lessons which we can learn from an organizational failure.

As noted in the Research Update (page 44) the doctoral research projects of Arthur Brooks and John Breda, which commenced in 1996, have taken longer to complete than originally contemplated, but both projects continue to look very worthwhile. Brooks recently finished his research and Breda should do so within a few months. The Institute is now considering publication plans. During 1996, the Institute was also pleased to become acquainted with a very interesting inquiry into the comparative organizational decision-making processes of three British orchestra organizations being carried out by Sally Maitlis, a doctoral candidate at the University of Sheffield. On pages 45 to 55, Sally describes her research project and presents some preliminary findings.

Musicians often complain that they are insufficiently involved in decision making within their organizations. Management complains equally often that musicians generally do not want to devote the time and learning required for such involvement and, further, that musicians don’t wish to have any responsibility for outcomes. Many musicians feel by reason of interest, education, and experience they could well be more involved in their organizations’ artistic policy and decision making. An eloquent commentator on this subject is James Orleans, a bassist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Jim is a knowledgeable champion of 20th-century music and a devotee of its role in revitalizing the orchestral repertoire. Especially refreshing in Jim’s message is a call to fellow musicians to become more active, assert more leadership, make a greater invest- ment, and assume more responsibility in their organizations.

The role of the “conductor”—especially when incorporated into the role of “principal conductor” or “music director”—is very significant in the dynamics of a modern symphony orchestra organization. The personal and professional attributes, behavior, and leadership of this position’s occupant can significantly influence the climate of the orchestral workplace. Many of the ambiguities of this organizational role go back some 150 years to the emergence of the “maestro” in Europe, as transplanted to North America at the turn of the century. Working together, Marilyn Fischer and Isaiah Jackson explore the historic myths and philosophies connected with this role and then postulate for it a new and more contemporary vision, along with some ways to implement that vision.

In a fitting sequence, Taavo Virkhaus stands back and critiques his role as a music director and guest conductor. Taavo points out the many mundane, earthbound, and mortal constraints of this job and how the times require a much more egalitarian approach—which the author applauds. At the same time, a central task of a good conductor is to inspire magical sound from an orchestra and good conductors must therefore possess some of that magic themselves.

With the score fragment on the cover, Phillip Huscher once again titillates our knowledge and our curiosity. A clue: the score’s composer had a significant role in the development of orchestral music and organization. Who was this unusual person?

Any manager or scholar interested in staying current with advanced organizational theory and practice is faced with a plethora of newly published books. A few are outstanding; many are interesting but repetitive; some are blatantly poor. Some have insights which easily carry over to symphony organizations; others have messages or approaches which are less obviously applicable. The vertical and horizontal compartmentalization within symphony organizations has long been intriguing. These well-marked “boundaries” exist in many organizations, including some of the largest and most bureaucratic. The Boundaryless Organization: Breaking the Chains of Organizational Structure explores these organizational patterns in a very readable and effective way, and the observations have special applicability to symphony organizations. We recommend this book to our readers, who will find a taste of the content on page 93.

We continue to welcome manuscript ideas and submissions and stand ready to provide editorial suggestions, from broadly conceptual to very detailed. We sense that many participants want better functioning symphony organizations, are developing greater awareness of the possibilities of organizational change, and have insights and ideas to present. We hope more and more people will use Harmony as a forum for these thoughts and suggestions.

On page 96, we are pleased to publish additions to a bibliography of research and writings about symphony orchestra organizations. We will continue to pub- lish extensions of this bibliography in each issue of Harmony and will publish an updated cumulative listing this fall.

Readers continue to send in encouraging thoughts about Harmony pre- sentations and Institute direction. On page 97, you will find some recent comments. We hope readers and observers will continue to send in suggestions and impressions.

On page 100, we list those symphony orchestra organizations which, as of March 10, have committed to 1997 support of the Institute. We thank you! With this issue of Harmony, we hope to gather additional support and present a longer list in the fall. If your organization is not in the list, please have the proper person fill in and return the Supporting Organization Register bound into the back of this issue. A suggested level of contribution support for 1997 is given in the table on page 101.

If you are a symphony organization participant, we encourage you to have Harmony mailed directly to your home or office. To do so, fill out and send in the postcard inserted in this issue or telephone, fax, or e-mail your request to us. If you are a nonparticipant and wish to have an individual or group subscription, there is an application for that purpose bound into the back of this issue.

Lastly, we can all benefit from a reminder about the pronouns we tend to use and the positive or negative effect they can have on those around us. So, as you view the inside back cover, remember that “practice makes perfect.”

Top

New Institute Governance Plan

With the experience of its first year of operation, the Institute has refined its governance structure.

As noted on the inside front cover, a small Board of Directors has been estab- lished along with a single larger Board of Advisors which succeeds the two smaller advisory groups formed at inception.

The Board of Advisors will consist of up to 15 persons who are or have been active participants in or close observers of symphony orchestra organizations and who support the goals of the Institute. Twelve of those positions have presently been filled. Advisors individually and as a group will have the following duties:

◆ ProvideongoingadvicetotheBoardofDirectorsandmanagement,as individuals and as a group, as to the general direction, programs, and policies of the Institute, and critique specific questions, ideas, and proposals.

◆ Exchangeviewswithfellowadvisorsanddirectorsandstayabreastof industry organizational developments.

◆ Collect views from colleagues and other participants in and observers of symphony orchestra organizations about industry developments and about the Institute and its programs.

◆ Promote an interest in and support of the Institute and its programs. ◆ Foster positive organizational change and greater effectiveness in symphony orchestra organizations.

The initial advisors will be appointed for terms running from the date of acceptance in 1997 until June 30, 1998. Thereafter, terms of continuing or successor advisors may run for one, two, or three years. It will be a goal over coming years to achieve approximately evenly staggered three-year terms of office for advisors in order to achieve greater institutional continuity and commitment.

The Board of Advisors will be composed of symphony organization board members, executive directors, orchestra members, and other orchestral organization participants and close observers, in about even proportions, and representative of various organizational sizes and locations. Although the Institute may make exceptions, the Board of Advisors will not normally have more than one member affiliated or formerly affiliated with the same symphony orchestra organization and, in order better to assure independence of view, will not normally have a member who was also in an executive role with an industry group or association.

It is anticipated that the Boards of Advisors and Directors will be linked electronically for regular ongoing communications and occasional single-event communications. The Board of Advisors will have one face-to-face general meeting per annum and during the year will have meetings among smaller groups for specific purposes.

The Board of Directors will consist of up to seven persons, five seats being presently filled. The Board will have all the normal powers and responsibilities of a Board of Directors under Illinois law. It will generally oversee the management and operation of the Institute, meeting periodically during the year to carry out its duties. In addition, the board will serve as a nominating committee for members of the Board of Advisors.

Top

The Turning Point by Lawrence Tamburri

A roundtable discussion with members of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra

EDITOR’S DIGEST

The Turning Point

We all like to read success stories, stories about changes that work. Just such a story awaits as you begin to read this issue of Harmony. Our story

opens with an introduction, written by Paul Judy, that describes briefly the history of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra (NJSO). Beginning in the 1970s, it is a history replete with organizational and financial conflict. Fortunately, it is history!

In Their Own Words

The story continues, picked up at the turning point, as related by seven members of the NJSO orchestral family. These seven came together to participate in a roundtable discussion of when, how, and why successful change occurred in their organization.

What you are about to read is an edited transcript of their discussion, one in which musicians, board members, and staff consider the elements that were involved in making changes happen. It is an encouraging recital, related with great candor, that touches on organizational aspects of the NJSO ranging from board structure to musician-staff relations. Each participant offers a different point of view, but all agree that the inclusion of musicians in decision-making processes was a critical element in this organization’s success.

And a Word of Caution

In a coda which follows the roundtable, Paul Judy sounds a cautionary note, reminding us that the NJSO still faces substantial external challenges. But his parting shot is upbeat, “It is a reasonable bet that this organization will be successful.”

The Turning Point

The New Jersey Symphony Orchestra (NJSO) was founded in 1922 and has antecedents which date to 1846. The organization adopted its present name in the late 1930s, a decade during which many players in this

orchestra were also regular New York Philharmonic musicians. From its inception, the NJSO has played an extensive repertoire and has performed music with some of the world’s leading concert artists.

After World War II, the orchestra began to play for audiences of all ages at various venues in and around Newark, its base city, and at locations throughout New Jersey, as it developed significant and growing state financial support (which continues to this day). As Samuel Antek, who served as music director from 1947 to 1958, said of this period, “. . . the relationship between the orchestra and community becomes ever closer and more meaningful. The days of royal patronage and the rich ‘angel-backer’ are passing . . . orchestras must be supported by the broadest cross-section of people. . . .”

In 1960, the budget of the NJSO was $60,000 per year, a number which grew to more than $250,000 by the mid-1960s. By the early 1970s, the budget had more than tripled; a significantly expanded performance schedule exploded costs to unsustainable levels. This overexpansion led to major operating deficits which were soon followed, during the 1973-1974 season, by an abrupt cutback in performance weeks, from 36 to 23. Along with the operating and financial crisis came mounting musician and organization tension and changes in administrative and artistic leadership. As a musician who participated in this period of organizational conflict said:

I am someone who had a basic benevolent spirit when I joined the orchestra, but I lost it. I can’t overstate how hurt, how angry I was— as a musician, as a human being with feelings—that the orchestra was being run so ineptly, with such short-sightedness, with no attempt to utilize the positive abilities of the people who were working here, all of whom wanted things to get better. . . . I was invited to attend a board meeting during this period and it showed me how closed-minded and inflexible our board was. The board felt that we musicians had nothing to communicate that would be of any positive use in terms of moving the organization forward.

Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, the NJSO’s financial statements were “qualified” by the orchestra’s auditors due to ongoing operating deficits and questionable operating ability. The orchestra went on strike briefly in 1979 over an artistic matter. In the 1980-1981 season, performances were suspended and the following season, performance weeks were again cut drastically, from 31 to 11. In early 1983, the music director and the orchestra parted ways. However, despite a decade of financial and leadership turmoil, the orchestra continued to display a high level of artistry and ensemble as evidenced by the excellent reviews which its regular Carnegie Hall appearances received.

Over the nine seasons ending in 1991, the organization again experienced very high revenue and cost growth, along with regular operating deficits.

But despite steady physical and artistic growth, the NJSO organization continued to be characterized by compartmentalization, disconnection, and tension among musicians, music direction, management, and governance. It also suffered chronic financial shortfalls. The overall attitude, commitment, and vision of the board was viewed by a thoughtful musician and confirmed by a staff member as “active in its passivity.”4 The board operated with modest knowledge of orchestral operations and with no effective oversight of management. In the mid-1970s, for various well-intentioned reasons, the NJSO instituted the practice of having two persons share board leadership. But by 1990, this practice led to serious ambiguity about the responsibility and accountability of this central volunteer function.

In late 1990, another crisis was emerging. In the words of another musician:

[It was] immediately before 1991 that the crisis began. The board was holding fast to a plan that would have cut our compensation by 47 percent. We were in a play and talk situation, there was almost no negotiation going on, and very little communication. We wrote letters to every board member trying to describe our frustration with the lack of contractual progress, attempting to humanize our situation, and explaining that a 47 percent pay cut was really going to impact our families, our lives, and our affiliation with the symphony. Many people were considering leaving music or the symphony in order to make a living. The board was a solid, evil, dark, ominous entity that we did not deal with well. Victor Parsonnet, who was on the board but not yet chairman, was the only person who answered every single letter he received. This was the first hopeful sign that perhaps someone was hearing our message. It was a very important turning point.5

Beginning with that turning point, NJSO participants should tell their own story to readers of Harmony. The Symphony Orchestra Institute asked several of them to sit down together and think out loud about what has transpired in their organization since 1991. What follows is an edited transcript of that roundtable discussion.

Lawrence Tamburri: Paul Judy asked us to come together to share our thoughts about what has changed in the NJSO since 1991, and why. To get us started, let’s go around the table and briefly introduce ourselves. I’m Larry Tamburri and I have been the executive director of the NJSO since 1991.

Randy Hicks: I am principal tympani with the NJSO and have been a member of this orchestra since 1971.

Bob Wagner: I am principal bassoon and chairman of the orchestra committee. I joined the orchestra in 1979 and have served on three negotiating committees and a couple of renegotiating committees.

Victor Bauer: I am vice president for finance and treasurer for the NJSO and the former president of Hoechst Roussel. In the late 1980s, one of my colleagues who represented our company on the NJSO board invited me to attend a concert. I liked what I heard and when the symphony started their chamber concerts in New Brunswick, I took a subscription. I have been going to concerts ever since.

Karen Swanson: I am general manager of the NJSO. I joined the symphony right out of school in 1986 as an administrative assistant. In the intervening years, I have served as assistant orchestra manager and orchestra manager, as well as serving for six months in 1991 as acting executive director.

Lucinda (Cindy) Lewis: I am principal horn and also secretary of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians (ICSOM). I have been a member of the orchestra since 1977. When I came to the NJSO, I had previously performed in Israel and had no experience dealing with an American orchestra.

Victor Parsonnet: I am chairman of the NJSO and have been since 1991. I am currently Director of the Pacemaker and Defibrillator Evaluation Center and Director of Surgical Research. For 27 years I was Director of Surgery at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center.

Tamburri: Let’s assume that those who eventually read what comes of this conversation have been briefed about the history of our orchestra and understand that we had some very troubled times. So I wonder if we can talk about a defining moment that caused things to come to a head and move in a different direction?

Swanson: Within one year, in 1991, we had a new executive director, a new music director, and a consolidation of board leadership when the roles of president and chairman were merged into one position. That was a defining moment for me. Victor Parsonnet isn’t just chairman of the board. He has grown up with this orchestra and truly approaches it with his heart, not just from a business standpoint. Zdenek Macal brought us strong artistic vision and, Larry, you brought us an openness that is not driven by ego. Macal articulated this best when he got up on the podium and said, “The past no longer exists. Forget about it. Go on to tomorrow. Stop talking about yesterday.” I think that because the three leadership positions changed simultaneously it was possible to leave the past behind us.

Parsonnet: While I agree with Karen about when things started to change, I think there are other elements that are important in trying to identify a defining moment. We made a major effort to include the musicians in all of our planning processes, our committees, and particularly in our board considerations. Musicians also served on the search committee for a new music director and for other important appointments.

The appointment of Zdenek Macal as our conductor was a stroke of good fortune. He, I, the executive director, and the general manager act as a cohesive, admiring, and cooperative unit. The level of cooperation between musicians and the board has increased to such a level that many of the musicians make contributions to the annual fund and contribute their time and effort toward reaching out to the community.

I would characterize the relationship among the board, the staff, and the musicians as one of colleagues working together for the same goals, rather than as employer-employee relationships. A true sense of affection and appreciation exists among us and is something of which we are quite proud.

Tamburri: Bob (Wagner), I get the sense that you think the defining moment was earlier.

Wagner: The defining moment for me was observing Victor Parsonnet’s level of commitment and energy. He stepped in and took real leadership of the board. He also asked some of us musicians to join in the interviewing process of executive director candidates which I think Larry would agree was different from the standard arrangement.

He explained to us that he saw little difference between running a hospital and dealing with doctors who are highly skilled professionals and running an orchestra and dealing with musicians who are highly skilled professionals. He has taught us that it is not a “labor-management” situation because we are all educated, creative people who can work together to find solutions.

The inclusion of musicians in the decision-making process was a great sign for us and did a lot to energize people like me who had become pretty cynical. I know it is difficult for some musicians to even consider trusting board members and I am sure it is just as hard for some board members to trust the musicians. We still have an ongoing project to facilitate the goal of just knowing one another.

Tamburri: You just touched on something that always bothers me. You said Victor taught us that it is not a “labor-management” situation. You don’t like to be considered labor and I don’t like to be considered management. I always look at it as the staff, not the management.

Wagner: You are right, Larry. I don’t think of us as “labor.” Maybe we’re “the help,” but we are also the product. We are the reason this organization can function at all.

Hicks: I think it takes a long time to get beyond the concept of “labor- management” because it is very deeply rooted, in my view. I am not exactly a radical and if I have trouble with this change, imagine how musicians to the right of me must feel. Even if they had 52-week, $100,000-a-year contracts, they would still feel ill at ease. It is also possible that there are board members who are still locked in the old roles. It is the unique problems we find ourselves facing that will bring rise to new relationships among the three groups.

Swanson: Actually, Randy, it is four groups. We can’t forget the audience. I want our concert goers not to see just “the orchestra.” I want them to get to know Randy Hicks—not just “that guy playing the tympani.”

Hicks: I think the board recognizes that the people who come to our performances are an asset and that the orchestra is something that is part of them. So I agree with you that we should try to get away from the label of “the audience.”

Tamburri: Let’s change the focus of this conversation a bit. The very fact that we are sitting here having this conversation means that the NJSO has musicians, staff members, and board members who talk with one another. We’ve mentioned the fact that I was interviewed by musicians as part of the search for an executive director and I also know that musicians had a great deal of influence in the hiring of the music director. So the question is: can we identify what we have done to improve communications? Remember, the whole point of this conversation is to share our story with the hope that it will make life better elsewhere in the industry.

Bauer: One of the prime problems we had in 1991 was communication. I think the staff had a pretty good idea of the problem points, but in general they were not able to communicate in a way that was understandable to someone who did not have all of the background. Given enough time, anybody can get the facts and understand them, but the key is to be able to communicate important information quickly.

For example, at one time the NJSO had trouble even generating numbers, let alone having a clear picture of its finances. Our financial organization is now much stronger and I think one of the things we have tried to do in the last four or five years is to find ways to communicate information about our financial condition to everyone. We may not be very good at it yet, but we are doing better.

Swanson: If you are looking for specifics, I think the “brown bag lunches” that we have with the orchestra between rehearsals are a good example of new ways to communicate. It is great when you join us, Larry, but it is even better that Victor Bauer has come to almost all of them. Because the numbers are always such a big issue, it is important to have someone who really understands them available to explain them to the orchestra. Having Victor with us in an informal setting brings a sense of truth and honesty.

Tamburri: Extending our thinking about communications, I have a question for Bob (Wagner). You have been coming to board meetings as long as I have been here. Would you prefer that musicians actually sit on the board as voting members or is it better this way?

Wagner: I am a proponent of maintaining a real distinction. I think musicians should be on the stage. I don’t want board members on stage. We musicians don’t have a role on the board unless we are able to go out and raise the dollars that the NJSO needs. That is the role of the board.

But just as I welcome board members at concerts and rehearsals, I appreciate being welcome at board functions. The fact that I can speak about anything I wish with the board is sometimes helpful, sometimes disturbing. But to have the opportunity to share the concerns of the musicians with the “final decision- making body” of the orchestra is very valuable.

Because individual personalities are involved, I am not sure that all musicians would feel comfortable being involved at the board level. It is the staff that must facilitate musician involvement and keep it at the forefront of the organization.

And I think it is important for those who read the transcript of this roundtable to understand that what we are doing here is not perfect. We have a long way to go and it is an ongoing process. Right now we have 15 or 20 musicians who are very committed and are willing to volunteer their time to help the organization. We need to find ways for more musicians to volunteer and know that their time is not being wasted; that they are not just there for “show.”

And even when two musicians serve on a committee, there is no guarantee that everything that is said in a committee meeting is communicated to all 70 musicians. The only guarantee is that two musicians know what was said. That is not good communication, just a beginning. Victor (Bauer) is right. We are only learning how to communicate and we have a lot of improvement to make.

Swanson: But even so, when we have a problem—whether it is financial in nature or broader than that—musicians are brought into the process. And my sense is that most of the musicians feel that even if they have not been directly involved in the discussion, they have colleagues who have been involved and will be informed of truly important items.

Hicks: In a way, better communication really hasn’t taken long to achieve. As a member of the orchestra, I can speak personally about the fact that we musicians can be a little lackadaisical in admitting how far we have come in terms of communication.

I think we need to remember that because of our proximity to New York City, this organization has never really been penalized artistically for not doing what it was supposed to do. Any other organization that has been through what we have been through probably would have just vanished. But our musicians can hold their noses and take gigs in New York to support themselves.

There is still a sizable minority of the orchestra that has not been won over. They are not willing to commit themselves and let go of their freelance mind sets. It is possible that when we move into the new hall (the New Jersey Performing Arts Center), some of the people who are reticent about letting go of their ill feelings will relax and want to become more engaged.

Tamburri: Let’s take a different tack and talk about how the contract affects communications. I have worked in organizations where the operating mode is that if you have the letter of the law on your side, you don’t communicate about an event that is going to occur because the other side just has to live with it. Here, we tend to focus on what the impact of a decision is going to be and to communicate with the proper people.

Several times a year, things happen where we believe our decisions are right according to the contract. Yet, Karen picks up the phone and calls someone on the orchestra committee to explain what we see coming up and to ask what they advise. From my experience, this is not typical in most symphony orchestra organizations.

Swanson: Larry, that cuts both ways. Over the past few years, the leadership of the orchestra has been strong and Bob (Wagner) and the rest of the committee have also been committed to maintaining a high level of communication.

Tamburri: I think a lot of trust goes into building this kind of relationship.

Wagner: I think we are such a small organization that we cannot afford to be factionalized. We all have to be focused on the same thing . . . to create the greatest music possible from the group of musicians on the stage at the time, regardless of venue.

Swanson: I don’t think a big orchestra can afford to be factionalized either. Wagner: I agree.

Hicks: They can get away with it longer.

Tamburri: Again, realizing that we are trying to think out loud in ways that might help others in our industry, can we identify any specific factors that explain why this orchestra has survived when others have not?

Wagner: I don’t know if I am going to answer your question, but I want to say that exorbitant guest artists’ fees have had a serious negative impact on our small orchestral institutions. More and more, our musician colleagues are forced to leave the profession because there is not enough work; there are not enough symphony orchestras to keep us in music. I guess I want to know how you find the sense of purpose within the organization.

Lewis: That’s part of the problem. Let’s look at some orchestras that have failed and some that have survived. The situation for the San Antonio Symphony is similar to ours. Both have had financial problems and internal union problems, but both have continued to exist in spite of deficits that should have put them out of business. This is true primarily because their boards—no matter how strong or weak they were at the time—really did want the orchestras to survive. There was at least some commitment to continue these organizations’ existence.

Contrast these situations with San Diego and Sacramento which have gone completely out of business. In those instances, the contention among the parties was so significant that nothing could be done to save them. Everybody was so entrenched in his own position that it caused an orchestra’s undoing.

The important point is that you have to have the right chemistry among the people who are involved. For the NJSO the deciding moment was when this chemistry came together. It was almost like a star was born and then an event occurred which caused the star to become a planet. This orchestra finally evolved from being a factionalized organization to one that had a common vision. Without a common vision, no orchestra is going to grow.

Tamburri: Lucinda, are you saying that only through fate can symphony orchestras reach this point? Are there actions that people can take to bring organizations to this point?

Lewis: I don’t know if unity can exist except when the personalities provide for it. It is important for boards to be autonomous because they are the ones that are responsible for governance and for raising the money. Musicians are responsible for producing the sounds that go into the product that we provide for the public.

But it is helpful for us to know what the board’s and the institution’s problems are. It is also important for the board to understand what our problems are as artists. That is how you make the institution stronger from both sides. But if your leaders don’t have the personal security to be honest with one another, it won’t work.

We all know of boards that have very paternalistic views of their orchestras.

How many times have we heard board members quoted as saying, “We are doing our best for the musicians”? Which brings up the question: who owns the institution? We all need to remember that it is a public trust. It does not belong to the board. It does not belong to the musicians. It does not belong to the staff. It belongs to the public and we are the professionals who provide a service to the public.

What can we do to make it work? I think everyone needs to be willing to expose themselves for what they are and to say what we personally can do to make the organization better. It is the willingness of each party that will determine how well it will work.

Tamburri: Victor (Bauer), are there models in the business world which we can emulate to strengthen our organization?

Bauer: Let me say that I believe that one member from the orchestra and the executive director should be full members of the board. But it is not an important enough point to argue about.

There are some management objective parallels that I do see. Most corporations have profit objectives and focus on things that provide income for the owners. Cultural organizations are a little different. For example, the idea of running deficits is probably not unreasonable—governments do it all the time— as long as you can find a way to pay your bills in the process.

The idea of communicating, or to use the current management buzzword, “empowering the employees,” is really trying to move the decision process out of senior management levels and down to whatever level has the information available to make a reasonable decision. This thinking supports the idea of having musicians on all of the major committees and on search committees that are musically directed. But we still need to recognize that there is no sense in being on a committee just for the sake of being on a committee. And in this orchestra, there are not a lot of committees that do hard, day-to-day work.

Tamburri: I would like you to think about one final question. I have heard over and over in this conversation that much of what we have achieved is a direct result of the personalities involved. What if those personalities change? What if this Victor decides to move to California and the other Victor decides to move to Hawaii?

Bauer: It won’t happen. But you have identified something that this whole organization needs to work to solve. We need to identify more people who are interested in music and who have the time and the ability to be on the board.

Tamburri: I agree that the board has to create the culture internally for the orchestra. I do believe that you can create a culture over time that will perpetuate itself but that doesn’t just happen in two or three years. I have seen it happen and it is the only way we can have a healthy symphony orchestra. Creating that culture is beyond the musicians and really must be left to the trustees.

Having said that, I want to thank each of you for your contributions to this conversation. When we read back over what we have said, I think we will find that we are strong people who hold strong convictions. We are also convinced that our collective actions are more important than our individual actions. These are the elements which we can identify that have made a difference for the NJSO.

A Look Ahead

As of early 1997, the external challenges facing the NJSO are substantial. State and federal funding reached a peak of $2.3 million in fiscal 1989 and then declined to a current level of approximately $1.2 million. Operating deficits increased significantly over the five seasons ending in 1996 and were financed primarily by increased borrowings. In 1995, a special grant from the state allowed the NJSO to retire outstanding borrowings and substantially reduce its accumulated operating deficit. Operating costs continue to mount and growth in performance revenues and private contributions is vital.

In October 1997, the NJSO will take up residency in the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, currently under construction in central Newark. This move will require even higher levels of audience support. But the leadership of every key unit in the NJSO organization appears to be cognizant of the benefit/cost/risk relationships of this venturesome move.

It is generally agreed that the NJSO would not exist today without the new levels of communication, involvement, participation, trust, and leadership initiated five years ago. Long-standing and high orchestral artistry continues to be a primary asset. As a total organization, the NJSO appears ready for its large external challenges. It is a reasonable bet that this organization will be successful.

Trust

To round out the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra story, we asked Larry Tamburri to “mull over” how he saw the role of executive director in today’s symphony orchestra organization, and especially any priorities he believed should be followed. Larry’s thoughts are captured in the following brief essay.

–Publisher

Symphony managers are blessed with being able to work in organizations brimming with highly creative, intelligent, motivated, and successful people: musicians, conductors, trustees, and staff members. Corporate executives envy the richness of our human resources. Yet away from the stage, an ironic lack of harmony plagues American orchestras.

Is there a catalyst which might ignite this human potential? Peter Drucker tells us, “Organizations are based on trust.” In this context, trust connotes a steadfast mutual confidence in and reliance on character and ability, and in the completeness, veracity, and proper use of the information that organizations disseminate.

In one of his books, Tom Peters states: “Trust. It’s the single most important contributor to the maintenance of human relationships.” Our industry is labor intensive. Presenting our artistic product to our audiences requires the efforts of many people. Just as the members of the orchestra must trust the musical convictions and gestures of the conductor to achieve a satisfying performance, all members of our organizations must trust the organizations’ leadership—the chairman of the board and the executive director. These leaders begin, as all leaders do, by setting examples.

The executive director of an orchestral organization holds the unique position of nexus: the point in the organization where the various components of the institution—board, music director, musicians, staff, and volunteers—intersect. The executive director can display trust in the institution and its decision-making processes by sending a message that unilateral decisions are to be avoided and building institutional consensus is our practice. Those who adhere to this principle quickly learn that building trust is not as simple as autocratic management. It is time consuming, less ego gratifying, and for some, the apparent lack of control is frightening, if not intolerable. Building trust is a long-term investment in the health of the institution.

John Naisbitt and Patricia Aburdene observe, “The manager’s new role will be to create a nourishing environment for personal growth in addition to the opportunity to contribute to the growth of the institution.” It is the executive director’s responsibility to work with and help develop the board, creating an organizational culture that will foster a healthy self- perpetuation of the institution. This can be accomplished through the board’s selection, nomination, and election processes. Building trust is a key to the creation and maintenance of such a culture. Committed, responsible trustees will beget committed, responsible trustees.

As its name implies, trusteeship involves trust. Ultimately, institutional trust is measured and dispensed at this level, since the board holds final authority in symphony orchestras. It is understood that trustees support the symphony through concert subscription and attendance, meeting participation, advocacy, and personal financial support. But the musicians and staff also watch to see if the board reaches critical institutional decisions through a reasoned, honest, and open discussion of the issues. Is the board weak? Does it acquiesce to an autocratic chairman, executive director, music director, or a demanding orchestra committee? Organizations develop confidence and character through the examples of their trustees’ behavior. Board membership means responsibility not just to the organization, but also to the board itself, to the staff, to musicians and to the music director.

Recently, influential members of the media have regularly expounded the notion that American orchestras are in desperate straits. While the degree of the problem and the accuracy of the facts may be debatable, it is clear to all of us that our industry is undergoing change and enduring a protracted period of instability. Peter Drucker states: “One has to make the organization capable of anticipating the storm, weathering it and in fact, being ahead of it. . . . You cannot prevent a major catastrophe, but you can build an organization that is battle-ready, that has high morale, and also has been through a crisis, knows how to behave, trust itself, and where people trust one another.”

In our personal lives, in business, and in orchestras, change is rapid, rampant, and inevitable. Coping with the pace of change is the most severe challenge symphony orchestras face. To be successful, our institutions need to be flexible in order to react quickly and intelligently to this mercurial environment.

Our institutions will be able to cope with the changing environment if they develop philosophies of shared vision based upon trust. The major stakeholders— trustees, musicians, the music director, and the executive director—must agree that the art form is important to our civilization and that it must be perpetuated. Everyone must agree to move forward in a spirit of openness and collaboration. Trust is much more than being truthful when queried; it cannot be built on passivity. Trust implies relying on one another and taking chances. The ore of today’s world—information—needs to be made available to everyone. In the “Information Age,” tools exist to ensure the continual free flow of information. It is our responsibility to use those tools.

Some will consider it naive to place such an emphasis on building trust, working collaboratively, and developing a shared vision. But there is much evidence that in both for-profit and nonprofit institutions, long-term organizational stability and strength are built on trust. Orchestral organizations are replete with exceptional human resources and their future success will be determined by how well they marshal this human potential. Creating an institutional culture based upon mutual trust is the first step which these organizations must take if they are to be strengthened and preserved.

Lawrence Tamburri is Executive Director of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. He holds an M.A. in music education and an M.B.A. from Arizona State University and a B.A. in music history from Duquesne University.

I believe in dispersed leadership. The days of the star system are over and every thriving productive organization has many more than one leader. The designated leader (CEO) of the organization looks at the leadership tasks, and determines that there are some leadership tasks that can be dispersed across the organization. Some people call this the empowerment of the people; I prefer dispersed leadership because Drucker notes and many of us agree, leadership has little to do with power, and everything to do with responsibility. When we share responsibility across the circles of the organization, we are building a powerful leadership corps. When we disperse the leadership it takes nothing away from the CEO; instead, it infuses a new kind of energy within the organization. At the Drucker foundation we say, “Our job is not to provide energy, it is to release energy.” I think the great leaders of now and in the future are going to be the leaders who find the key to releasing the energies and spirits of their people.

Frances Hesselbein

Drucker Foundation News, April 1996

EDITOR’S DIGEST

Symphony Orchestra Volunteers: Vital Resources

Volunteers. No symphony orchestra organization can function without them. But are they necessary evils or vital resources? Decidedly the latter in the mind of Mike Gehret, Vice President for Marketing and Development for the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra.

Gehret has been involved in nonprofit management for more than 25 years, including service with three large-budget orchestras. In his essay, he shares practical and proven ideas for making optimal use of volunteer resources.

Philosophy First

The essay begins with a recitation of the philosophical underpinnings of Gehret’s thinking about volunteers and how to involve them successfully in institutional marketing. He then explains that while there is a temptation to think that involving large numbers of volunteers will free staff members’ time, just the opposite is often true. He argues that there are few shortcuts available to staff if volunteers’ time is to be used wisely. He also explains why it is important that every volunteer have a “point of contact” to turn to for answers, advice, and help on projects.

Finding, Training, and Keeping Volunteers

Much of the essay is devoted to detailed descriptions of the actions required to find, train, and keep volunteers. Gehret suggests that when the process works, it is circular—volunteers who truly understand institutional marketing and produce successful programs attract favorable publicity, which in turn fuels successful fund- raising campaigns, thereby attracting more capable volunteers, and leading to even more successful programs.

Setting Expectations

The theme of the essay then turns to expectations. Gehret explains that both volunteers and staff need guidance as they perform tasks to support the orchestra. He also reminds readers that using volunteers wisely includes making time for just plain fun. Returning to the philosophical tone with which it began, the essay concludes with a series of questions for future consideration.

The careful review of using volunteer resources wisely which this essay presents should provide food for thought for orchestral volunteers at all levels, staff, and musicians alike.

Symphony Orchestra Volunteers: Vital Resources

The roles of volunteers in nonprofit organizations and, more specifically, in the development process are the subject of volumes of writing. Furthermore, symphony orchestra volunteers receive extensive attention,

particularly from the American Symphony Orchestra League (ASOL) in Symphony magazine and in the work of the National Task Force for the American Orchestra as reported in “Americanizing the American Orchestra.” Each year, workshops, presentations, and panels at meetings of the ASOL and state orchestra associations are devoted to the recruitment, organization, and utilization of volunteers in the orchestra field.

This focus on volunteers reflects both the important roles which volunteers play in the governance and operation of symphony orchestras and the frequent frustration which volunteers and staff alike feel when volunteer resources are not well used or when they are inadequate to the task. While most of us involved with symphony orchestras understand the musical resources needed to mount a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 or Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand, the human resources—both volunteer and staff—necessary for the development function to be successful are less well understood. In fact, I would guess that the human-resource needs of the development program remain a mystery to all but a small group of executive directors, senior development staff, and trustee leadership. These needs are most certainly a mystery to many orchestra players whose activities are so dependent on the adequacy of such resources.

The editors of Harmony asked this author to take a fresh look at the employment of volunteers in the institutional marketing of symphony orchestras and at attitudes and approaches needed to obtain and maintain those resources. My views on the subject are formed by more than 25 years of nonprofit management experience, including nearly 20 years in institutional marketing for three large-budget orchestras. The following set of assumptions underpin these views:

◆ Symphony orchestras function best when they are truly volunteer-centered and when ownership of the organization rests with the board of trustees on behalf of the local community. The board alone can hire and fire the music director and the executive director; thus the board members have, and must accept, direct responsibility for the quality of the artistic product and for the quality of the management. Board members and other volunteers are at the center of policy-making and goal-setting processes. When volunteers are involved in this way, policies and goals become those of the whole organization, not just the staff. I know of no exceptions to this assumption.

◆ Development is not just fund raising and marketing is not just selling tickets. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) has a Department of Marketing and Development, which might just as easily be called the “Department of Institutional Marketing.” Volunteers and staff engaged in the CSO’s institutional marketing program work to help create a positive climate around the institution so that it can raise money, sell tickets, and successfully achieve the artistic goals of the orchestra.

◆ On every level, successful institutional marketing involves building relationships. The more personal those relationships, the easier it is to create a favorable climate around the orchestra. The large numbers of potential ticket buyers and contributors who must each be reached and the unique positions that volunteers, as distinct from staff, have in the community, dictate the important role which volunteers must play in the relationship-building process.

◆ Orchestra volunteers, by definition, are not compensated financially. They choose to volunteer for a variety of reasons and it is important for management to understand what motivates each volunteer. The competition for volunteers’ time and dollars is increasing; volunteers are choosing more carefully the organizations for which they will work, and the work they will do. Volunteers want to be involved— and should be involved—in making key decisions and they insist on staff support of high quality.

◆ There are no “tricks” to suggest in successfully involving volunteers in institutional marketing; there are few truly “new” ideas in working with orchestra volunteers. Rather, volunteer programs are successful because they follow a well-designed plan which relies on volunteers and staff who are devoted to the orchestra, work hard, communicate openly with each other, and pay attention to detail.

Volunteers are commonly involved with orchestras in governance activities; in direct service activities, including fund raising, ticket sales, and event production; and as advisors to the orchestra leadership in areas of special expertise, such as management consulting, and on legal and accounting issues.

The first challenge orchestras face is defining the roles which volunteers will play in each of these areas, and then determining what sorts of volunteer resources are needed to fill those roles. Several conditions must be met before this can be done. First, staff must be clear about their own roles before they can help define volunteer roles. Second, there must be important tasks for volunteers to do and they should be tasks at which particular volunteers have some likelihood of success. And third, there must be an institutional commitment to providing adequate resources to staff the orchestra’s volunteers.

The Need for Staff Support

While it is tempting to assume that involving large numbers of volunteers will free up staff time, in reality, large volunteer forces require a great deal of staff support. In fact, there is often a tendency to underestimate the staff resources necessary to provide adequate support for a large, active, and involved group of volunteers. Involving volunteers, particularly new volunteers, in the life of the orchestra is a labor-intensive activity and there are few shortcuts.

Determining appropriate staffing levels is one of the more interesting challenges that development professionals face, particularly because it is usually difficult to determine the economic contribution of a particular staff member. I also question how useful it is to apply general formulas to specific institutions. Can one generalize to the extent of saying that Orchestra X should spend 5 percent of its total budget on development; or that Orchestra Y needs 1 staff member for each 100 volunteers? Probably not.

But what is clear, at least here in Chicago, is that the economic rewards of a strong volunteer program are considerable. Data currently being gathered for a new CSO long-range planning process have helped us to look beyond the dollars raised by volunteer solicitors and through special-event fund raising. Preliminary figures show that 1,425 volunteers have contributed twice as much cumulatively over their lifetimes as 13,360 subscribers who are not volunteers. Even more impressively, the average amount donated over a lifetime by each volunteer is nearly 18 times larger than the amount donated by nonvolunteers.

The Importance of a “Point of Contact”

When we look at those volunteers whom we have been successful in involving, we find that each has at least one, and probably several, strong points of contact within the organization. A “point of contact” is the person to whom the volunteer knows he or she can turn for answers, for advice, for help on a project, or for other kinds of assistance. While that person is sometimes a volunteer, it is more often a member of the staff. If staff resources are inadequate to provide sufficient points of contact for each volunteer, the result may be a shrinking volunteer pool or a group of volunteers with many inactive members.

In the volunteer-centered orchestra, the institutional marketing staff maintains a collaborative and supportive relationship with volunteer leaders. Staff members work with volunteer leadership to set priorities that are consistent with larger institutional goals and that recognize that not all challenges and opportunities are equally important. They help

volunteer leadership to manage the larger body of volunteers and they help energize volunteers when enthusiasm and motivation begin to lag, as inevitably happens from time to time. They also furnish technical knowledge, supply clerical and other support services, furnish information, and keep records. Finally, the staff fills these functions while placing the institution’s volunteers at the center of activity—and in the spotlight—while not seeking attention for themselves.

Decisions regarding the employment of volunteer resources ought to be corporate decisions; they should be made jointly by staff and volunteer leadership, not by one group or the other acting alone. Written job descriptions can be helpful when there are questions about particular volunteer and staff roles.

However, in orchestras where volunteers and staff work successfully as a team, such questions do not often arise, nor do such questions as, “Which volunteer or which staff person has the final authority to make this decision?” Similarly, “crediting” issues (deciding which staff or volunteers get the credit for bringing about a particularly positive event or for meeting a particular goal) occur less frequently in orchestras in which volunteers and staff work as teams. In most successful orchestras, there is enough good news for everyone to share in the credit.

Finding Volunteers

Where do symphony orchestras find their volunteers? First and foremost, they find them among the ranks of concert goers. Volunteers are motivated by a variety of factors including sheer altruism, a need to socialize and be with other people, developing professional contacts, social panache, and getting specific kinds of experience or training. Orchestra volunteers usually become involved because they are devoted to symphonic music and have strong emotional ties to the local orchestra. A majority of orchestra volunteers have had some formal musical training.

Enlisting a new volunteer is not at all unlike asking someone to make a contribution. Like most successful fund-raising calls, effective volunteer recruiting evolves from an existing or a newly established personal relationship. There is an adage among development professionals: large gifts result from the right person asking the right prospect for the right amount at the right time. Similarly, volunteers are more likely to enlist when asked to do so by the right person at the right time for the right reasons and in the right way.

Whether the orchestra is searching for potential trustees, solicitors for a capital campaign, or volunteer docents for an educational program, the first question

asked should be, “Who attends our concerts?” This line of thinking leads to recruiting new volunteers through ads in the program book, special events focused on music and musicians, and mailings to subscribers and frequent single-ticket buyers. It points to the importance of referrals, both from members of the orchestra “family” (those who already volunteer, as well as staff and musicians), and self- referrals. In the case of potential trustees and other volunteer leaders, this thinking suggests a preference for involving those for whom music and the particular orchestra are an important focus of their lives, rather than those for whom service is a community responsibility or the means to make particular social and business contacts.

In this respect, the process of identifying and recruiting orchestra volunteers is circular. Volunteers become intimately involved with all aspects of institutional marketing. Successful institutional marketing programs generate great amounts of favorable publicity about the orchestra, sell more tickets, and fuel stronger and more successful fund-raising campaigns. Favorable results help to attract greater numbers of the most capable volunteers, leading to ever more successful programs.

Kent Dove, in his book Conducting a Successful Capital Campaign, suggests some factors in the successful recruitment of key volunteers, which are paraphrased below. These factors are as applicable to governance volunteers, advisory volunteers, and other direct service volunteers as they are to capital- campaign volunteers. They include:

◆ Involving appropriate volunteers and staff in asking someone to volunteer. Peer-to-peer volunteer recruitment is just as effective and necessary as peer-to-peer solicitation.

◆ Meeting personally with the prospective volunteer at a time and place that can allow for an unhurried discussion.

◆ Beginning with the case statement for your orchestra and for the particular program for which you are asking the person to volunteer. People respond to opportunities and to vision.

◆ Describing the job being offered clearly. Written job descriptions are often a good idea, especially to the degree that they force the institution to think about its volunteer staffing needs and organization. Additionally, it is useful to describe how the prospective volunteer is uniquely suited to fill this position.

◆ Outlining staff and other resources that will be provided to assist the prospective volunteer in doing her or his job.

◆ Assuring the prospective volunteer of support from other key volunteer and staff leadership.

◆ Estimating the amount of time needed to do the job. The best volunteers are often the busiest; they devote large amounts of time to things that are important to them. If you try to downplay the time and energy necessary to do the job, the prospective volunteer might turn it down as not being demanding and important enough to be worthy of her or his time.

◆ Explaining how the volunteer will be involved in setting goals. If goals for the program have already been set, help the prospective volunteer understand how the goals were set, and that they are attainable.

◆ Answering questions fully and honestly.

Training and Educating Volunteers

Once volunteers are enlisted, training and educating them become the keys to their successful involvement in the orchestra. The written materials provided for volunteers and such activities as volunteer orientations require thought and attention. However, the most important factor in training and educating volunteers involves inculcating them with the culture of the institution. This activity is so critical that it cannot be left to a volunteer handbook or single orientation event.

The institution’s culture can be passed along to new volunteer in many ways. For instance, many nonprofit organizations have experimented successfully with volunteer mentors. New volunteers, whether trustees or direct service volunteers, are assigned a volunteer “mentor” who is intimately familiar with the organization. The mentor takes responsibility for making sure that the new volunteer understands how the institution functions and introduces her or him to other volunteers and staff. Mentors play an active role for the first three to six months of a new volunteer’s involvement and remain available for consultation after that time.

In addition to information provided through orientation sessions and publications, other activities can provide opportunities to pass along information about an orchestra’s history and culture:

◆ regular meetings of trustees and other volunteer groups;

◆ receptions for new volunteers;

◆ formal or informal gatherings of volunteers and staff to work on particular projects;

◆ tours of the concert hall, backstage area, and administrative offices; and

◆ individual and small group conversations.

Whether new volunteers can be quickly and successfully integrated into the orchestra “family” often depends on how well and how quickly they come to understand the institution’s culture.

Some volunteers will resist the idea of “training,” perhaps because they have been involved in a similar volunteer role for another institution or because they are resistant to having someone tell them how to do their jobs. Several techniques can help overcome such resistance. First, training should be interactive, with many opportunities for feedback from those being trained. Second, when possible, experienced volunteers should do the training, in addition to or in place of staff. And third, role playing works well as a training technique, particularly when training volunteers to ask for contributions.

Setting Expectations for Volunteers

Once volunteers are in place, there are certain expectations that the orchestra’s volunteer leadership and staff can legitimately apply.

◆ Volunteers have the same responsibility as staff to complete whatever tasks they have agreed to do in a timely, accurate, and thorough fashion.

◆ Volunteers recognize that they are the orchestra’s representatives in the community. They are in a unique position to advance the orchestra’s interests in contacts with friends and business associates; and they are also in a position to do the orchestra harm by making negative comments about the organization and its programs or about other volunteers or staff.

◆ Volunteers should be well informed about the orchestra and its programs. This is, of course, a two-way street, as the ability of a volunteer to become and to stay well informed depends on the orchestra’s programs for volunteer orientation and education and on how well it communicates with the broad range of volunteers.

◆ Volunteers should work with staff as partners and colleagues. They should keep staff informed of the progress of their tasks; they should inform staff if something occurs which affects their willingness or ability to do the job; and they should consult with staff before departing from an agreed-upon plan.

◆ Effective volunteers willingly step forward to support the orchestra with their own financial resources, as well as their time. Fund-raising volunteers, in particular, cannot ask for a gift until they have made a gift themselves.

Just as importantly, there are expectations that orchestra volunteers legitimately apply to the staff and volunteer leadership.

◆ Volunteers want to help the orchestra. But they want some things for themselves, too, including timely information about the orchestra and its programs, direct contact with music and musicians, appropriate training for tasks in which they are engaged, and exposure to a variety of interesting and enjoyable experiences.

◆ Volunteers expect to have a role in institutional planning and decision making at an appropriate level. They want to work as team members with volunteer leadership and staff; they do not want to be thought of as “free help.”

◆ Volunteers—as a function of the volunteer/staff partnership—look to staff to keep them informed of progress on tasks in which they are jointly engaged and of any factors which affect these tasks.

◆ Volunteers want and deserve appreciation and recognition for the service that they provide. Orchestras could not survive, at least not as we know them, without the volunteer leadership and technical expertise, the financial support, and the countless thousands of hours of labor which volunteers provide.

And someplace in our consideration of how we obtain and utilize volunteer resources, there must be room for fun. Enjoyment of what one does is a prime motivation for volunteers and responsibility for making sure that volunteers enjoy the tasks that they agree to do rests squarely with the volunteer leadership and the staff.

Questions Answered; Questions Raised

All that said, where are we left in our understanding of the human resources which we employ in institutional marketing in the service of our orchestras? A close reading of the preceding thoughts will raise at least as many questions for the attentive reader as it will answer. Some additional questions it has caused me to ask, and perhaps attempt to answer in some future article, are as follows:

◆ Are there orchestras whose musicians are successfully involved in the institutional marketing process? If not, should musicians be involved, and how should we go about getting them involved?

◆ How should we go about “importing” good ideas in institutional marketing from other kinds of institutions, such as colleges and universities?

◆ How can we deal with the systemic problem of underinvestment in development? Can we establish some useful standards for development investment that can be widely applied to a variety of orchestras?

◆ How can we establish a development culture in each symphony orchestra organization, raising the awareness of development programs and goals among each member of the orchestra “family,” and creating a role for each family member within that culture?

◆ Are our volunteer groups aging at the same rate as our audiences? Assuming that we need to enlist younger volunteers, are there special approaches that we need to take to reach them? Will our volunteer structures need to be revamped to accommodate the different lifestyles of young volunteers?

It is clear that volunteers play vital roles in symphony orchestra organizations. In strong orchestral organizations, volunteers are effective partners of staff and trustee leadership, providing service across a wide range of activities. Every member of the symphony orchestra “family” needs an understanding of what treasured commodities volunteer resources are. As the Symphony Orchestra Institute works to improve the effectiveness of symphony orchestra organizations, perhaps the thoughts I have shared here will help orchestras develop policies and plans that are inclusive and that use volunteer resources wisely.

Michael Gehret is Vice President for Marketing and Development of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Prior to joining the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, he served for 12 years as Development Director for the San Francisco Symphony. He holds an M.A. in higher education administration from Columbia University and an A.B. from Princeton University.

Top

An Instrument of Knowledge

Drawing fresh attention to ideas and insights previously revealed but of enduring value and worthy of renewed reflection is one objective of the Symphony Orchestra Institute. What follows is an analysis of events which occurred slightly more than 10 years ago.

In September 1986, the Oakland (California) Symphony Orchestra Association declared bankruptcy. In May 1987, Melanie Beene & Associates was selected by a group of institutional funders “to provide a detailed analysis of the issues surrounding the dissolution of the Oakland Symphony Orchestra Association.” (p. v)1 The report was published in January 1988, and was entitled Autopsy of an Orchestra: An Analysis of Factors Contributing to the Bankruptcy of the Oakland Symphony Orchestra Association. The study involved in-depth interviews with more than 70 individuals, analysis of extensive institutional records, careful organization of large amounts of data, and quite thoughtful presentation of facts and interpretations by the consulting team.

From one perspective, Autopsy is a story which was developed by and for the people of Oakland, to review and provide “feedback” about the demise of a central, cherished, community institution in which, as participants, supporters, or close observers, many had been involved. In this sense, Autopsy is a sensitively prepared, caring introspection for local study. The report undoubtedly helped many Oakland citizens better cope with the reality of the death of a beloved institution and for some, assistance in framing their own participation in that process. Even after 10 years, this essay may bring back uncomfortable and unresolved memories.

From another perspective, we believe the insights in Autopsy should be of keen interest to all who participate in today’s symphony orchestra organizations or, more generally, to participants in nonprofit organizations which depend on broad community and philanthropic support. Indeed, this more universal purpose was clearly intended by Autopsy’s funders as noted in their preface:

The consultants have made a serious effort to capture the compelling story of the Oakland Symphony in sufficient detail to enable volunteers and professionals elsewhere to identify operational patterns which recur throughout the nonprofit sector and in their organizations specifically. It is intended that this study be a working document, a management tool, an instrument of knowledge which can be generalized broadly. (p. iii)

Essays previously published in Harmony have dealt with the organizational structures and processes which need change in many North American symphony orchestra organizations. This essay presents a number of the issues related to these workplace structures and processes and then draws on Autopsy—as a well-documented, classic case study of a symphony orchestra organization which failed—to illustrate the “operational patterns” which were being followed, with tragic consequences. Of course, the reader must then ask the unpleasant question: “Do any of these patterns exist in the symphony orchestra organization in which I participate?”

Two other matters deserve mention. First, the authors of Autopsy note that mistakes and failures by specific individuals were irrelevant to the purpose of their study. For this reason, we have chosen, in our quotations, not to use personal names, employing role or job titles instead. Secondly, given the purpose of our presentation, we have organized and sequenced our topics and extracted quotations in ways which differ from the order followed in Autopsy. However, we give page references for each quotation so the reader may trace our quotations to the particular section and page in the source document.

With these introductory thoughts, we hope that this essay will help Autopsy become “an instrument of knowledge” for all participants in symphony orchestra organizations. — The Authors

Historical Overview

The Oakland Symphony Orchestra Association was founded in 1933. In its first season, it presented four concerts in the lobby of the local YMCA (the Association later moved to the Oakland Civic Auditorium). The founding conductor served for 24 years, until his death in 1957. Two music directors served until 1971, during which time the season expanded from eight concerts per season to twenty- four. In 1964, a youth orchestra was founded within the Association and it achieved international recognition by the mid-1970s. In 1966, the Oakland Symphony received a Ford Foundation matching grant of $1.35 million, one of 61 orchestral grants awarded.

Starting in 1971, under the leadership of a fourth music director, the Association expanded its season to 33 concerts, initiated a pop series, commenced a youth concert series, started an in-school educational program, and gave free concerts in public places to reach more diverse audiences. The orchestra also undertook other organizational and programming innovations which led, in 1977, to a national award for adventurous programming.