Teaching, Learning, Experience (III)

Photo: Andrew Hurlbut/ New England ConservatoryOutside NEC’s Jordan Hall, there is a giant poster depicting one of our students, a young violinist playing with obvious emotion and concentration on a superbly sculpted, Picasso-esque electric violin. She is surrounded by at least a dozen wine glasses with different quantities of liquid in them — which has caused many observers to quip that it must have been a great party!

In fact, the violinist is performing a challenging contemporary work, “Black Angels” by the American composer George Crumb. Completed in 1971 and scored for electric string quartet, the work requires the four string players to sing, shout, play glass harmonicas (hence the wine glasses) and various percussion instruments. The idiom reflects a world torn by religious and political strife and the torment of the Vietnam War. Crumb called it “music in time of war.”

At the performance in NEC’s Jordan Hall, the reputation of the work had preceded it and the audience listened with the type of rapt intensity only tragedy and deep emotion can elicit. The performance seemed to speak for itself; the work did not seem to need a program note or a long explanation from stage, even given its advanced language and unconventional instrumentation.

BUT, would it have benefited from some explication? Were the listeners’ very positive reactions unique to a specialist audience in a conservatory? How would an audience have reacted in, say, Albuquerque or Portland, Maine? Would those listeners have needed more preparation in order to enter fully into the expressive universe of the music?

It’s difficult to say, but the experience of Black Angels at NEC reminded me of the astonishing address that my good friend and colleague Eric Booth gave as my keynote speaker at Commencement last May. Eric is the quintessential teaching artist, an actor by training (including performances as Hamlet, he informs me), an agent of change and invention with a passion for enquiry and empowerment. On top of all that, a true mensch.

Photo: Andrew Hurlbut/ New England ConservatoryIn his remarks, Eric encouraged the graduating students to become “agents of artistic experience.” It is not enough, he asserted, to play or sing something with drop-dead virtuosity. Rather, the goal of the artist is far more ambitious: “The audience has to reach out from themselves toward us, and you reach out toward them with your performance, and if good things are happening…, people do what I describe as the single most important thing in the arts… They don’t just admire, or recognize, or appreciate (all good things, but side benefits); they …enter the world you are offering with your best heart and skill and make a connection that matters to their lives.” Such revelation is the entire point of art, Eric said, and it is the artist’s responsibility to make that revelation possible.

Then, he offered several possible performance scenarios. Four times, he read William Carlos Williams’ poem, “The Red Wheelbarrow,” each with a different set-up. This is the poem:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

It was the first rendition that caused me the most reflection. Eric said: “…for this first performance, I’m going to provide no preparation, the way it is usually done in music. We just come out and let you have it.” And, just as he surmised, many listeners — I among them — were left somewhat mystified by the poem until Eric evoked the specific biographical context in which it was written. Without Eric’s amazing insight and explanation, this minimalist collection of ideas and images never would have coalesced into a meaningful, emotional poem for me.

However, Eric’s advocacy for such audience preparation also raises questions about the effect of explication on the work of art itself — questions that aren’t really new. Some artists and aficionados are adamant that it is the work itself that will and should convince you and bring you into its realm of meaning, just as happened with the NEC performance of Black Angels. Think of Gustav Mahler, who withdrew the seductively programmatic movement titles in his Third Symphony or Claude Debussy who placed the titles of his piano Preludes at the end of each piece. Their intention, I think, was to assure that the music spoke for itself, offering the listener a far more expansive horizon of meaning than a narrowly focused title might allow.

The English poet Philip Larkin has said: … a poem is “a verbal device” that preserves an experience indefinitely by reproducing it in whoever reads the poem. … it seems as if you’ve seen this sight, felt this feeling, had this vision, and have got to find a combination of words that will preserve it by setting it off in other people… the impulse to preserve — the experience, the beauty — lies at the bottom of all art.”

To those of this persuasion, any commentary, be it in a program note, a pre-concert talk, an audio guide — or even a poetry reading — is effectively circumscribing the work and imposing the speaker or writer’s interpretation on the audience’s experience.

On the other hand, concert programmers, teaching artists like Eric Booth, armies of program annotators, and museums with their rental headsets believe that audiences today lack experience and confidence in approaching an art work. They believe it is their duty to provide explications through all sorts of access points, guiding audiences to understanding that they would never have discovered for themselves. And to judge by the popularity of pre-concert lectures, audio guides, and other instructional materials among audiences, they might be right.

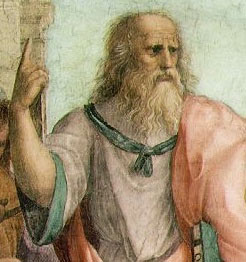

I have amused myself by imagining this polemic (what a great word! It comes from the Greek polemikos, relating to war) embodied in the personae of Eric Booth and the Greek philosopher Plato, sitting over an amphora of wine in downtown Athens. Plato’s Socrates (B.C. 470 to B.C. 399), of course, never wrote down a single word.

Image: Creative CommonsEverything he did or taught was oral. In fact, Socrates actually denounced reading and writing as he felt that such practices would destroy our most valuable intellectual ability — our memory. While Eric would have argued in favor of providing explication for a work of art like William Carlos Williams’ poem, Plato’s Socrates would likely have taken the opposite position. With his clear idea that poetry is provided to us by the muses and is not rational, the philosopher would have dismissed Eric’s exercise in explication, just as Socrates demolishes the claim of Ion, the “rhapsode” and exegete, that he could know and explain Homer. (If you would like to read more on this topic, there’s an excellent online summary in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy here.

I, myself, find both arguments persuasive — up to a point. (Perhaps that’s a kind of Platonic dialectic?) And both can result in revelation that is art’s compelling raison d’etre. So, maybe the resolution of the polemic is, at least in the short term, to offer those intriguing and captivating gateways and access points, to explicate with sensitivity so as not to unduly restrict the compass of a work. We may well need this if the fine arts are to survive. And, for the long term, the answer is — of course, what else? but so desperately elusive! — a better, richer, life-long education for all people so they become more resourceful and confident audiences, more receptive to the transformation promised by art.

In the mean time, I imagine Eric and Plato in the guise of Socrates holding forth at the Academy, eagerly anticipating the post-debate celebration. And my money’s on…

Leave a Comment: