The Detroit Symphony

About the Orchestra

The Detroit Symphony Orchestra is noted for its magnificent Orchestra Hall, its extensive discography of recordings, its wonderful relationship with so many outstanding music directors, and its first-in-the-country radio broadcasts. By all counts, the DSO is doing very well indeed, yet not only the city of Detroit but the entire state of Michigan seems to be in the throes of a depression that is leading the rest of the nation. How is it thriving?

The DSO was founded in 1887, with a first concert at the old Detroit Opera House. (The orchestra shut down from 1910 to 1914, so some histories claim 1914 as the founding date.) The DSO has had a very prestigious list of music directors, including Russian pianist Ossip Gabrilowitsch, who oversaw the building of Orchestra Hall, which opened in 1919.

I’ll let Paul Ganson (page 2), the official Detroit Symphony historian, tell you more of the details about the history of the orchestra and the amazing way in which Orchestra Hall was saved from demolition.

I’ll just summarize quickly by listing some of the more prominent music directors: Paul Paray, Sixten Ehrling, Aldo Ceccato, Antal Dorati, Gunther Herbig, and Neeme Järvi. The DSO is preparing to welcome Leonard Slatkin as their next music director, after a five year hiatus of guest conductors.

The Detroit Symphony gave the first symphonic radio broadcast in 1922, recorded over 70 records with Paul Paray from 1952 to 1963, and finally moved back into Orchestra Hall in 1989, much to everyone’s delight. Again, I’ll let Paul Ganson tell you how a group of concerned citizens managed to save Orchestra Hall, and develop the entire city block into a performing arts center.

Anne Parsons (page 3), Executive Director, describes the intriguing relationship the DSO has with the community in terms of owning a block full of buildings, and inviting the community in to use their facilities as well as attend concerts.

Charles Burke (page 4), Education Director, and Randy Hawes, Bass Trombone (page 5), talk about the wonderful education and community engagement programs the DSO has nurtured for many years, and describe the recent Power of Dreams program started with a million dollar grant from Honda.

Emmanuelle Boisvert (page 6), concertmaster, and Robert deMaine, principal cellist, talk about their experiences of being members of the DSO. Emmanuelle, celebrating her 20th anniversary, describes her enthusiasm for Maestro Slatkin’s arrival and her fond memories of previous music directors, and Robert talks about the difficulty of actually joining the DSO, and his early memories of DSO radio broadcasts.

And finally Shelley Heron (page 7), oboist, describes the relationship between the musicians and management, and gives some history of their recent negotiations.

–Ann Drinan, Senior Editor, November 2008

Interview with Paul Ganson

Paul Ganson joined the DSO bassoon section in 1969, and retired in 2004. For 20 years he was President and CEO of Save Orchestra Hall, an organization founded to keep the wrecking balls from destroying Detroit’s famed symphonic hall. He is known as the historian of the Detroit Symphony and, indeed, is working on a book about the orchestra.

Describe Orchestra Place in Detroit for us.

We own two things – Orchestra Hall itself, which extends 180 feet from Woodward Ave, and the rest of the block. On the remainder of the block is the Max M. Fisher Music Center, which was built to provide the facilities that Orchestra Hall lacked.

In 1993, Peter Cummings, son-in-law of Max M. Fisher, a developer from Montreal, built Orchestra Place. It has a 5-story building with a 4-level parking deck in the block immediately next to Orchestra Hall. We realize income from the net rental proceeds, and have use of the parking structure.

The Detroit Medical Center has administrative offices there, and the University of Michigan has created a Detroit footprint with 14-15 schools. They also use the space for students from Ann Arbor to come practice architecture and city planning in Detroit.

How did you come to lead the campaign to save Orchestra Hall?

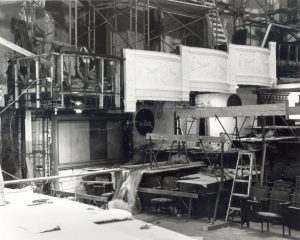

On September 17, 1970, a bank security guard looked across the street and saw ladders on the side of Orchestra Hall (it was boarded up). He alerted Richard Magon, the Leasing Director for the Professional Plaza, who discovered that the men with the ladders were from the Water Board. The building had been sold at noon and they were preparing for the final disconnect because Orchestra Hall was to be demolished within two weeks. Dick Magon telephoned me and a committee was formed to save the building.

Orchestra Hall was built in only 4 months and 23 days in the summer of 1919, at the beginning of the Roaring Twenties. In 1939 the orchestra, having suffered greatly in the Depression, chose to move out of Orchestra Hall. [Ed. Note: They moved into 3 different venues, and finally settled in Ford Auditorium on the riverfront for 33 years.] In the winter of 1987, the DSO decided to move back into Orchestra Hall, which was a wonderful decision. It’s a marvelous hall.

With the founding of the campaign to save Orchestra Hall in 1970, I had to learn all the history of the orchestra and the hall. I relied on the feelings and memories of the people who had experienced the original Orchestra Hall, and then those who knew the building as the Paradise Theater, when it was the home of great black jazz players from 1941 – 1951. The hall then had the diversity that the DSO is always seeking. One of our hallmarks is that we do a lot of programs to acknowledge, encourage, and reward diversity.

What was the connection between the campaign and the DSO?

The Campaign to save Orchestra Hall was totally separate from the DSO. Their decision to move back into the hall began in 1987 when other plans could not be brought to fruition and the DSO began to look at the possibility of moving back into the hall. At that time, in the next block south of the hall, Winkelman’s (the woman’s department store) main office and warehouse were located next to Orchestra Hall. I discovered that they were about to move!

I was just about to leave on tour when I got a call from a reporter for the Downtown Detroit Monitor, asking about Winkelman’s moving. I knew nothing about it, so I called the President of Winkelman’s and expressed an interest in acquiring their building. Ultimately they did donate it, about a year later. It was a gift worth about a million dollars. It was on that land that Peter Cummings created Orchestra Place.

[Editor’s Note: Here’s a wonderful website describing how Paul and his campaign saved Orchestra Hall!]

Tell us about the actual opening of Orchestra Hall after it was saved.

Opening night was in 1989 – Yo Yo Ma played at the opening. He had played in the hall with the Detroit Chamber Music Society and loved it.

Actually the first subscription concert of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra was on December 19, 1887 – a Monday evening at the Detroit Opera House. Detroit is the 4th oldest orchestra in the country. Detroit itself was founded in 1701 – it’s a very old city, especially for a midwestern city.

Please share with us some interesting historical facts about the DSO.

Well, over the long history of the DSO, there have been some work stoppages, and the orchestra has gone out of business more than any other orchestra in the country, so thus it has come into business more than any other orchestra in the country.

The orchestra closed down from 1910 – 1914, during the 1942-43 season, and again from 1949 – 51. In celebration of Detroit’s 250th anniversary, it was started up again by John B. Ford in 1951. (He was a member of the Ford family known as the Salt Fords, who made their fortune from rock salt used in glassblowing). Under his Detroit Plan, all the principal corporate sponsors in Detroit pledged $10,000 annually to the orchestra.

The DSO was the first symphony orchestra ever to broadcast on radio – it first broadcast on February 10, 1922 with pianist Artur Schnabel, and appeared on the Ford Symphony Hour from 1934 to 1942. Ten year ago, we were heard by more people than any other orchestra, as part of the General Motors “Mark of Excellence” broadcast.

How is the orchestra prospering in the 21st century?

Everyone involved – musicians, board, and staff – have tried to improve their relationships since the 1950s. Speaking from the musical side, there are at least as many people involved in as many committees as in any other orchestra. The pension plan committee has 3 musicians and 3 board/management members. The same is true of the music director search committee. Our contract has carefully tried to craft ways in which the members of the orchestra and the corporation and various groups thereof can work together in a constructive way.

Tell me about the DSO’s famed recordings.

The first was in 1927 with Ossip Gabrilowitsch for RCA Victor – he was a Russian pianist who studied with Anton Rubenstein. He and Neeme went to the same conservatory, though obviously years apart. We continued to record for RCA in the 1940s (1943-49).

Under Paul Paray in the 1950s, we were playing at Masonic Auditorium and Ford Auditorium, but we always returned to Orchestra Hall to make the recordings. These were done for Mercury Records.

Then under Antal Dorati we recorded for London Records. It was the beginning of the digital age – the DSO’s Rite of Spring recording won first Grande Prix du Disque for compact disc.

And under Neeme Järvi we did lots of recordings for Chandos.

Interview with Anne Parsons, President

Anne Parsons has been President and Executive Director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra since April 2004. Prior to coming to Detroit, she was General Manager of the New York City Ballet, General Manager of the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, and Orchestra Manager of the Boston Symphony.

Tell me about the DSO – what makes you unique in the world of orchestras?

This is my fifth year in Detroit– when I arrived the symphony was in the last year of Neeme Järvi’s tenure as Music Director and the search for his replacement was at a standstill. There was a lot to do; we had to know what direction the orchestra should take artistically. While searching, I spent a lot of time dealing with questions about our culture, such as what makes us unique, how does the orchestra fit into the community, and what is our vision for ourselves. All those questions were important to answer while we were looking for a Music Director. I felt we had to answer them before finally choosing a Music Director.

What makes us different is where we are: our relationship with our audience, with our community – the business, financial, and donor community, including local foundations – and with government itself. We are the largest arts organization in Michigan; we’re the anchor for the artistic image of the state. But we live in a city going through enormous stress, which puts us in an interesting position.

We have a big story to tell – we’ve always been a fighter organization. We’ve made changes in our lives on a regular basis since the early 20th century. The orchestra left Orchestra Hall in the late 1930s, went to the Masonic Temple, and then to Ford Auditorium to be in the middle of city. We returned to Orchestra Hall in 1989– it was a dramatic gesture because Orchestra Hall is part of the fabric of the DSO. We have a strong sense of self and mission, and of the role we play in the community.

Tell me more about your mission and the role you play in the community.

I now look at the Detroit Symphony as being in three buckets. The middle bucket is orchestra itself and our concerts. We’ve branched out in recent years and now have a very healthy Pops business. And we have one of the best concert halls in the world. We’ve added World Music programs, where the orchestra participates in some of the concerts. And the orchestra’s work in education – we perform Family concerts on weekends, and school concerts during the week.

The second bucket is the building itself and our partners. The Mosaic Youth Theater uses our venue, as do a number of corporate and foundation partners. Individuals use the building and our resources for their own needs and interests. For example, many weddings take place in the building, and companies like to use our space to launch products, like new car models. We have two other spaces for events in addition to the atrium – all in all, it’s a very versatile space. And we’re a major presenter of jazz concerts in the Paradise Theater.

We built the new building [the Max M. Fisher Music Center] five years ago and have expanded for several reasons. We wanted to provide services for our patrons (i.e., bathrooms, lobby space, atrium space, etc.) and also have a place to exhibit art and host other people’s functions. It’s a connector to our concert hall, but also a means for the community to use the building.

The 4-block radius near the music school is totally new – there’s a new market, a Starbucks, and other new establishments. The new building has had a very positive impact on the community. People convene there for all sorts of reasons and use the building as a resource. For example, last night a Nobel theoretical physicist met with a group to present a lecture on quantum physics. It’s a wonderful use of the building; I gave a short presentation about the DSO, but was followed by a physics lecture!

The third bucket is the education piece. I know you’re interviewing Charles Burke, our Director of Education, so I’ll let him tell you about the third bucket in detail.

What are your anticipations of Leonard Slatkin’s tenure as Music Director?

Leonard was not looking for a new Music Director post when he stepped down at National – he looking for a respite in life. But he’s a real fighter too, and he has a truly international vision. At the core of his passion is the importance of music education and music in the schools – not for the students to learn to be future musicians but rather to become appreciators of music and art at an early age.

We started our education programs years ago – as if it were in someone’s garage. We serviced 30 to 40 kids. Over the years we’ve grown into a program that trains 700 kids annually – the last 150 are thanks to the new Honda grant. Building an educational infrastructure is a business of the Detroit Symphony. The DSO has invested in this educational program, and some of our players teach there as well.

It’s a no brainer as to why Leonard chose to accept the position with the DSO – it’s because of the way we connect to our community, the value we place on education, the level of the orchestra artistically, and because we’re dedicated to our venue and organization.

What is your annual budget and how would you describe the financial health of the organization?

We’re struggling because of the economic downturn. Our annual budget is $32 million. We need to increase the endowment, which was over $90 million before the recent market crash. A local community foundation has over $10 million in trust for the DSO, plus we have our own endowment.

Artistically speaking, where is the DSO now and where do you think it is going?

We must be very careful going forward. The artistic vision must come first and foremost. We must focus on quality all the time, not quantity.

Our big focus is to grow audiences and find new audiences in younger and diverse parts of the community. We want to provide education for all people, not just people who are interested in learning the details of classical music but also those with a more casual interest. We must try to do it in a fiscally responsible way, using good business practices. It’s all in our strategic vision. There’s nothing revolutionary about it but it focuses on the honest and important values of this community. We want the DSO to be a good citizen of the community.

I’d like to see the DSO travel and record. We’ll need to raise money to do it, but it’s in our strategic plan. Our first tour will probably be inside the country – perhaps a Florida tour. But we’ve been receiving invitations from Europe, even before Leonard accepted the position. And we’re also open to going to China or the Far East.

On a personal note, I moved to Detroit from New York City and got completely hooked on this city. I’ve come to know the environment, met the people, read the history, and I find it completely compelling. To be asked to come to contribute to the history of a great organization is infectious. It’s a lot of work and there are a lot of challenges, but it’s for all the right reasons and it’s very rewarding.

DSO Education Programs

Charles Burke, Director of Education

What types of community engagement programs does the DSO have?

We have two main areas of programs. The first is exposure, which involves inspiration points. These might be a concert presentation or a master class – something that doesn’t have a long-term connection with an audience but where the scale may be very large. For example, our Family and school-day concerts involve large numbers – perhaps 20,000 single visits. Do those inspiration types of things have a lasting effect? They can be a catalyst moment upon which to build future things. But kids aren’t involved in presentation events.

The second type is training, and this is where we differ. Training is where we put an instrument in a child’s hand that will change their life. We have ten different youth ensembles ranging from classical to jazz to band: 3 full symphony orchestras, a string orchestra, 3 full big band jazz bands with a combo program (chamber for jazz), a classical chamber orchestra, and a wind ensemble. They all rehearse in the Pincus Music Center, which is an extension to the Max M. Fisher Music Center and includes a large rehearsal hall, practice studios, and office space.

Our curriculum is in pyramids – the base is the new program sponsored by Honda for classical music. We’re giving instruments to children, they’re learning how to play and taking lessons under our tutelage. We feed them up through our orchestra system.

We now have 730 students per week that we train, for an average of 30 weeks a year. When you include the parents, that’s 1,460 times 30, which equals many thousand contact points. With an engaged family, their perception of the DSO changes from that of a presenter to that of a service provider in the community.

What’s your relationship with the Sphinx Organization?

The two institutions have a great deal of respect for each other. We’re careful of how we program in the community so that we dove-tail and don’t compete. We sponsor their national tour, and host their local concert and two outreach activities. They are part of our marketing efforts, and we provide Orchestra Hall and box-office services.

Describe Honda’s million dollar gift and the Power of Dreams string project.

It’s our newest initiative for putting instruments into student’s hands. The Power of Dreams program has 150 third to fifth graders this year. It’s brand new – it’s in its fourth week. It’s not supplementing what’s happening in the classroom but rather it’s filling the gap of what’s not being offered. After all, if the DSO doesn’t do it, who will?

Our goal has been to build programs that are incredibly scalable. All the components of Power of Dreams in its first year can be replicated within any community in the US. It’s the American answer to El Sistema. I’m finishing up a book with journalist Nancy Mallots, Changing Lives through Music, which is a practical template to be the American answer to El Sistema. Many symphonies are taking over the administration of the local youth orchestra and are adapting them to fill the gaps in music education. The book is geared towards Executive Directors and Board members, and the philosophy is: if it can happen in Detroit, it can happen anywhere. [Ed. Note: the book is scheduled to be published in early 2009. Check Polyphonic for an early review.]

How do you get your message out to the community?

Moving forward, the question is how to use our capital (intellectual, political, and fiscal) to move an agenda to ensure that there are school music programs throughout the region. We’ve determined that the 3rd bucket Anne Parsons talked about is Strategic Advocacy. How can we change the conversation in a specific targeted community about the role of fourth grade strings? How can the DSO saturate that market and change the tone of the argument and be the tipping point in the community? There’s a difference from the beginning-level advocacy where you’re starting from scratch to preserving what’s there. And we plan to advocate all the way up to the state government. Leonard will be instrumental in making the program a success. He can be that tipping point that helps save music in the schools. We’ve also changed that argument in the community. They no longer see us as an institution standing on a pillar but see that we’ve rolled up our sleeves and are doing it. And are asking them to join us. It’s a much more profound argument – we’re not just a presenter but are truly a service provider.

Tell me about the DSO civic ensembles and the Detroit School of Arts.

The latter is a high school run by the Detroit public schools that is physically on DSO campus. Within it, there’s a 900 seat theater, a radio station that plays classical and Jazz, and TV station. It’s a relatively new urban high school. And there are challenges in terms of all different pressures! But it’s exciting to have the building on our campus.

How many DSO musicians are involved in your education program? You must use teaching artists.

It depends. 30% to 40% of the DSO musicians are involved. Ten years ago there wasn’t much interest. The musicians didn’t want to deal with some pretty elemental things. Now, with high level groups and a great variety of ensembles, some DSO players want to deal with the very best – they’ll hold sectionals, for example. Others want to teach instruments. We have a wide variety of intersection points; it’s not just about one program. And as the programs have grown and we have had success, I don’t have to ask so many times. It’s not so hard to recruit musicians now; they want to be part of a winning team. The real limit is their time and schedule.

What percentage of the DSO budget is all the education programs?

6-8%

How would you summarize the DSO’s (and your) educational and community engagement philosophy?

It’s a brand new idea and strategic planning has led us in this direction. We are very cutting edge – the difference is that we have the community as the nucleus of the organization. We provide lots of services, and are always reaching outward. We don’t have a strict organizational structure in place. Leonard will be instrumental in being a figurehead in our continuing outreach.

The big thing that separates us from other orchestras and what makes us cutting edge is our recognition of the three buckets. Our asset is not just the orchestra but also our buildings, our investment in the community, and having our educational institution under the umbrella of a cultural institution. The challenge moving forward is that the three buckets are similar but also very different. Where do they overlap and have commonalities, our model can be adopted in other communities.

Anne Parsons has really been leading in this area. Our high involvement in education changes the perception of the organization in the community, and alleviates the pressure on why someone should buy a ticket or support the DSO. We’re changing the landscape of the orchestra industry.

DSO Education Programs

Randy Hawes, Bass Trombone

Randall Hawes has been bass trombonist of the DSO since 1985. A Michigan native, he received a Bachelor of Music Education from Central Michigan University. Prior to joining the DSO, he was a member of the Kalamazoo Symphony, the Woody Herman Orchestra, and the Tanglewood Festival Orchestra.

Tell me about the musicians’ involvement in the DSO’s educational programs.

Over the years we’ve been involved in outreach programs, sending chamber groups out into the community. We have a brass quintet, woodwind quintet, a percussion ensemble, and string quartets, and we play in community schools in the greater Detroit area. We have a side letter to our regular contract that spells out the payments for each type of education service: master class, instrument demonstration, chamber performance, etc.

The majority of the orchestra members want to focus on performing, so education is a side vocation for most players. But everyone is very happy that our education program is so successful. 50% of the musicians are involved in some aspect of it. Charles Burke’s enthusiasm is outstanding. It has a very positive PR value and helps to build our future audiences. We’re interacting with the kids and fostering a love of music in them.

What’s your relationship with the Detroit School for the Arts?

We have an ongoing relationship with the Detroit School for the Arts, which is a public high school for about 800 kids that was built on land donated by the orchestra, so it’s right next to Orchestra Hall. The program is struggling a little bit right now as a result of the problems the Detroit public schools are experiencing. But anyone can attend the arts school – they just must show an interest in the arts. I have a few trombone students there.

The main problem with the school is that it lacks a healthy feeder program – Detroit doesn’t have music programs in the middle schools that can feed the high school with kids with established musical talent. But then it only opened three years ago.

The school has been a very positive thing in the city of Detroit. The arts are flourishing in their own way over there, and it’s just across the alley from us. I’m involved in a couple of chamber groups that perform and do master classes at the school. And the students get involved with the DSO – the kids come to a few symphony rehearsals, and their vocal group has performed with us on some Pops concerts. Many of the kids involved in the music program at the high school are also involved with the Civic Ensembles of the orchestra.

I hear Honda has given you a million dollars to start a new educational program.

The Honda Power of Dreams program is just getting off the ground. A few DSO musicians were involved in the auditions held for this program. The program uses 5 or 6 teachers from outside the orchestra, and is mostly for beginning strings. There wasn’t enough lead time for the DSO musicians to put the Honda program in our schedule because of the size of the program.

Down the road, as these kids mature and develop, we’ll start teaching them as part of our education program. Many of our members teach at area schools, including the University of Michigan, Wayne State, and others.

Tell me about the Education Committee.

We have great community leaders on the Education Task Force who are very involved and have connections with the school board and DSO board. There’s a lot of overlap, with good communications ongoing. The committee is mainly focused on the school for the arts – how many master classes they need, how many lessons, etc. There’s a new orchestra conductor, so we’re developing the relationship there. It’s an arts school but it’s also an inner-city school. The students are very needy – they need a lot of attention on varying level. Some of the ninth graders are just starting playing their instruments, while some of the older kids are pretty advanced. Hopefully that will smooth out over time.

We’re also finding our way in terms of the balance. We want to have enough of a presence over there to satisfy them but yet not upset the balance with the teachers and staff of the school. They may have a bit of a misperception that the orchestra is very wealthy and can afford to do anything. I wish that were true, but the programs we do have are very successful and rewarding.

Playing with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Emmanuelle Boisvert, Concertmaster

Emmanuelle Boisvert was twenty-five-years old when she became the first woman to win the post of concertmaster in the United States, and is celebrating her 20th anniversary in that position this season. She began her studies at age three at the Conservatoire de Musique de Québec, and attended the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she was a student of Ivan Galamian and David Cerone. Following her graduation from Curtis, she played for the Concerto Soloists Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia and the Marlboro Music Festival. While a member of the Cleveland Orchestra, she won her coveted position in Detroit in 1988.

This is your 20th anniversary year as concertmaster of the DSO. Do you have any special performances planned for this year?

I usually solo with the orchestra every season. This coming March we’ll feature the Alban Berg concerto under the direction of Leonard Slatkin, our new Music Director.

Three weeks ago, on the day of my anniversary, our previous Music Director, Günther Herbig, to whom I’m grateful for hiring me, was celebrating his 25th anniversary of joining the Detroit Symphony as he conducted Brahms’ 1st Symphony. He was Music Director of the DSO from 1983 to 1990. It was very emotional for me to experience his touch once again; it was like old times.

What are some of the highlights of your two decades with the DSO?

Our Music Directors – that is the person who’s got the paintbrush; we’re just the colors on the canvas. We’ve had great Music Directors over the year. Our 15 years with Neeme Järvi was a match made in heaven and a musical journey I will always cherish. We are so pleased now that Leonard Slatkin will be joining us after a five hear hiatus. Our opening concert with him in December will feature Carmina Burana.

We looked for a long time, and waited until we were sure that it was going to be an extremely exciting relationship. Leonard Slatkin guest conducted twice in recent years, at our summer venue Meadowbrook and at Orchestra Hall, and we knew, instantly, that he was right for us. Even though this was the first time he’d conducted the DSO in 20 years! His tenure at National Symphony was coming to a close, so the timing was right. And we hope his will be a long tenure with us – all our Music Directors have stayed for a long time. When it works and magic is created, there are no reasons to make a change.

Anything else you’d like to share about your experiences with the DSO?

Our education programs are extremely strong, with great participation among the musicians. We’ve not done any recordings or tours for five years because we didn’t have a Music Director. We made many recordings with Neeme – I very much enjoy listening to them. We will be more active again once Slatkin begins his tenure with us. It’s not just about the music we play, but also who is the maestro.

Robert deMaine, Principal Cellist

Visit Robert’s website for his complete biography.

When did you join the DSO? What was your first year like?

I joined the DSO in 2002 – six years ago – and I love playing here. My first official concert was on New Year’s eve. My trial week as Principal was in October of ’02. Neeme is fond of programming encores, so as a test for the new guy, the encore he programmed was Poet and Peasant but we just did the Poet part – just the cello solo part! As part of your trial week, you play a concerto with the orchestra. I played the Haydn D Major, which is a fearsome piece but I wanted to give it to them with both barrels!

The Detroit Symphony is notoriously difficult to get into – they hold multiple auditions and then don’t hire anyone. Slatkin is not in favor of multiple auditions, so this may well change.

How much turnover is there in the orchestra?

This year there was quite a bit, due to an unfortunate chain of events. Felix Resnick, former Assistant Principal Second Violin, passed away rather suddenly. He had been in the orchestra for 66 years! He did yoga, swam every day, and one day he got sick and he never returned. He suffered with pancreatic cancer and then he was gone.

We also lost four violinists to other orchestras. One went took a major administrative position at the National Conservatory in Beijing, another went to Minnesota as Principal Second, and the others to the Met and Chicago. Like any other orchestra not in the top 5 or 7, we like to think of ourselves as a destination orchestra, and it’s hard when we lose colleagues to other orchestras. Detroit obviously has a lot of problems as a city, but so do most large cities. We’ve been hit hard around the Great Lakes – we’re in the throes of a deep recession, the auto industry being what it is.

What do you think makes the DSO unique?

One defining unique characteristic of the Detroit Symphony is our national NPR broadcasts. We used to do 26 weeks and have now cut down to 13 weeks. (We might have 26 on one of the satellite radio stations.) The broadcasts are first rate. Ever since I was a kid, I remember hearing the DSO on the radio. I recently found a cassette tape of a concert I recorded on my boom box when I was 13 years old, so it was broadcast in 1985 or 86. The concert featured the 2nd Rodrigo Cello Concerto, played by Julian Lloyd Weber.

When you go to a DSO concert, you always gets your money’s worth. We always rise to the occasion, and our very best is equal to any of the top 5 orchestras. And we get lots of great guest conductors. [Charles] Dutoit was here recently – it doesn’t get any better than that.

Interview with Shelley Heron, Member of the Negotiations Committee

In 1985, Shelley Heron became a member of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and also joined the Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings. Prior to joining the DSO, she held the position of Principal Oboe with Orchestra London Canada and currently is a member of LakeWinds, a Canadian based woodwind octet. Shelley holds degrees from the University of Toronto and the University of Western Ontario. Her primary oboe teachers have been Jon Dlouhy, John Mack, and Richard Killmer.

What is the relationship between the musicians and management? Have you had any recent difficult negotiations? What are your challenges?

In late 2003 management came to us while we still had about 2 years left on our contract and asked us to renegotiate the final years. The result was a concessionary agreement through 2006. Following that, we negotiated a new 3-year package in 2006/7 – that was a very difficult negotiation that could be described as fairly hostile, and certainly it was concessionary once again.

The first attempt to negotiate that contract ended in a 1-year extension, and then we came back a year later and hammered out a 3-year contract. The process of doing that was not pleasant, not that we expected it to be. The ICSOM report of the process and results (found online on the ICSOM website, accurately reflects the tone and details of the negotiations. Our goal was to keep the DSO as one of the top 10 compensated American orchestras, thus retaining us as a destination orchestra. We feel we are on the cusp of becoming a stepping stone orchestra in which musicians regularly pass through on their way to achieving their goals. Both Pittsburgh and Minnesota have left us behind, and we’re now number 11.

The negative feeling coming out of the negotiations has not entirely dissipated yet. We’re certainly working on carrying in our consciousness that everyone in the organization must be respectful. We know that a hostile atmosphere is not productive if we hope to accomplish many of our goals.

Right now, I would say that we’re engaging in meetings and discussions, trying to improve communication and our working environment. DSO musicians have always been very collegial and collaborative onstage. Some personality conflicts are inevitable in any workplace but we manage to keep those under the surface. Performing with the DSO is a very positive experience and that helps us deal with the other difficulties.

What’s it like playing in Orchestra Hall?

We have a fabulous hall! We’re so very proud of Orchestra Hall and what it took to bring it back to life. I love coming back from a tour and sitting in our own hall and playing. The hall is a great unifier – management and also the board rally around Orchestra Hall as a landmark and the wonderful acoustic environment that it is.

Do you have a long-range plan going forward?

Coming out of the 2003/4 negotiations, we embarked on strategic planning, which was one of the issues the musicians felt very strongly about. Anne Parsons came in 2004. She took a little time to settle in and, within a year and half, we started planning. It’s been a very extended process because of problems with the 2006 negotiations.

The first planning effort went into hiatus because a conflict developed between elements of the strategic plan and certain elements of the CBA [collective bargaining agreement], including artistic issues such as the size of the orchestra, the quality of our guest conductors, and the fact that the musicians strongly believe we must maintain the DSO as one of America’s top 10 orchestras.

The strategic plan is practically finished – it’s in the final stages and we hope it will reach final approval in the next month or so. The economy in Michigan is not very healthy right now – we’re leading the nation in layoffs. We’ll get through this the best we can in the next few years, and we’ll come out the end a stronger organization.

The strategic planning process has been so important because board, management, and musicians were equally involved and the discussions, which often included Leonard Slatkin, were open and honest. This bodes well for the future of the DSO and for the relationships inside the organization. My hope is that this type of collaborative effort will translate into other areas of the operation. We know what we have to work on, we know where we want to go, we know what steps we must take in order to get there, and finally, there seems to be a willingness to move in a positive direction

What are your thoughts about incoming Music Director Leonard Slatkin?

We waited a long time for the right match and Leonard Slatkin is the right match for us. We’re all very positive about Leonard coming on board. He’s a ” hands on” music director and we are looking forward to his full-time attention. Currently, we are in a transition year in which Leornard is conducting 5 weeks only. Next year he moves to a full schedule at the DSO.

What are some of the highlights of your two + decades with the DSO?

For some musicians in the orchestra, touring provides the highlights of a career, but I live in Canada, am over an hour away from work, and I feel like I’m always on tour. I’m into great performances at Orchestra Hall, of which there have been many over the years. The most recent example I can provide was just last week when Charles Dutoit set the stage for a fabulous week of music making with the orchestra – it was a really energizing, hugely satisfying and inspirational experience.