Duende

I have always made it a policy not to miss an opportunity to hear great artists at the end of their careers.

Interestingly, it was a young pianist years ago who crystallized for me the preciousness of artistry enriched by a lifetime of discoveries and experience.

Mitsuko Uchida, then in her 20’s, had tea with me and another famous pianist who was about to turn 40. The 40-year old was deeply depressed because his birthday felt like a real turning point in his life, and he was audibly moaning. She listened attentively and courteously then said—and you have to read this with the most charming Japanese accent in mind, “Ah, I cannot wait to be 40. What would I give to be 40. Then to be 50. Ah, to be 50. It would be so amazing. What would I have become?… and then to be 60 – to be 60! Ah, life would open, glorious, everything known to me… She enumerated the decades. Finally: “And to be there on the day that you die. What would you be, what would you have become?” The soon-to-be 40 year old pianist was speechless.

But Uchida’s outburst left me thinking. I wanted to hear the great artists at the end of their performing lives. I wanted to hear what they had learned, what they were able to give.

The first musician in my quest was the great Polish pianist, Arthur Rubinstein. He was in his 80’s when I worked with him on a series of two recitals. I had never seen him live, only heard him on recordings or on television. The impression was of an eight foot tall god who could play better than Apollo. I met him at the train station in Cardiff for a recital at the New Theatre. I searched the train for my mental image of this physical colossus. I was with a female colleague, young, attractive and charming, who went off in the opposite direction in search of the maestro. I never found him. But she did. And I discovered them both, walking arm in arm like old lovers, moving boldly and briskly out of the concourse. The amazing power of charisma!

But the colossus I met was under five feet tall, with huge ears and a halo of white hair. For the recital, he never practiced. Just went to the Hall and looked at the piano. Perhaps a chord or two on the piano, but no more. His concentration during the concert was granitic. He sat and played with total love, focus, and the straightest back I have ever seen! He gave his considered view, in his 80’s, of the works he had loved his entire life – Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, Chopin.

He opened his world, touched by two centuries, by world wars, by suffering, discoveries, art, books, the power of European culture, good food and wine, the appreciation of beautiful women, and he presented his exposition of what he had seen and lived in these works. It was a journey for him as our pianist, a journey for the audience. It was difficult to know if he played the piano or the piano just presented its sound to him bidden by his mind and passion.

The great French cellist Paul Tortelier is little known in this country, although he started his career as a rank and file cellist in the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky. In Europe, he enjoyed an outstanding career as a soloist and recorded all the major repertoire, including two astonishing performances of the Strauss Don Quixote, first with Sir Thomas Beecham in the 1940’s and then much later with Rudolf Kempe. He was Don Quixote; tall, gaunt, strange, fantastical. I commend both recordings to you. I heard him play many times—the Dvořák and Schumann Concertos, recitals. But, on the most memorable occasion, he was 77 years old and, though we had no idea, he would die suddenly a couple of weeks after the concert. The concerto was the Dvořák, which he must have played a million times … but…it felt like a first performance. Fresh, original, and totally different from the performance I had heard him give only a few years earlier. He played every yearning phrase, every virtuoso embellishment, as though time and life itself waited on this moment. Then there were the encores. All solo Bach, and I know his solo Bach backwards.  I had grown up with recordings of them. But this was new. He was presenting his solo Bach now at this time in his life, with new thoughts and discoveries. It was breathtakingly different. He had maintained his curiosity to the very end and was still developing his great artistry, just a moment before his voice would be silent.

I had grown up with recordings of them. But this was new. He was presenting his solo Bach now at this time in his life, with new thoughts and discoveries. It was breathtakingly different. He had maintained his curiosity to the very end and was still developing his great artistry, just a moment before his voice would be silent.

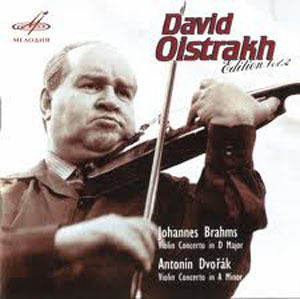

So to violinists… I have studied them so much over such a long period. First, David Oistrakh,

the great Russian who took the world by storm in the 1950’s with his elemental and earthy playing, his phrases full of the sound of vowels and consonants. So very different from the nuanced, perfumed playing of Heifetz, the dominant string player at that time. In 1973, I saw him play the Tchaikovsky Concerto  again a work he had lived with since childhood. This was just a year or so before his death. He was relaxed, bow arm in total control, chords played full force as though at the piano, sound as rich and unforced as you could imagine, and everything right. It was the small details, the little phrases, the nods to notes and colours no one ever thinks of. A true first performance after so much.

again a work he had lived with since childhood. This was just a year or so before his death. He was relaxed, bow arm in total control, chords played full force as though at the piano, sound as rich and unforced as you could imagine, and everything right. It was the small details, the little phrases, the nods to notes and colours no one ever thinks of. A true first performance after so much.

Oistrakh’s great friend Yehudi Menuhin, I also heard on many occasions. When he had found his rhythm, had relaxed as a player, he could deliver some of the most sublime insights into our art of any artist I have ever known. The Cesar Frank Sonata played as though it were a complete improvisation there on the spot, the Bach Gavotte en Rondeau from the E major Partita given such originality – every repeat of the Gavotte completely new and fresh with ideas, colours, weight. And then the Beethoven Concerto. He first played this when he was about 10, so when, I heard him he had had this in his repertoire for nearly 60 years. The sound, the originality, particularly in the slow movement drew you into the work’s heart. I have a DVD of him playing this from 1963 and I put it on as a special treat. The improvisation he makes of the slow movement is an example to every artist.

He first played this when he was about 10, so when, I heard him he had had this in his repertoire for nearly 60 years. The sound, the originality, particularly in the slow movement drew you into the work’s heart. I have a DVD of him playing this from 1963 and I put it on as a special treat. The improvisation he makes of the slow movement is an example to every artist.

And so to Nathan Milstein, perhaps the most naturally gifted violinist of all time. He lived and breathed the instrument, which had no secrets from him. In his last flowering from his mid 70’s, he gave an annual recital in London at the Royal Festival Hall. And every year it just kept getting better and younger, until he was nearly 80. I cannot forget this old, so young man playing his own Paganiniana and creating new improvisations right in the concert.  Backstage after the concert, the doyen of British concertmasters, the wonderful Hugh Bean, stood in line with me for Milstein’s autograph. He went up to the great violinist and said “Maestro thank you so much for still playing like this.” Now that got a tear or two. You can see Milstein’s autographed program book in my office at NEC.

Backstage after the concert, the doyen of British concertmasters, the wonderful Hugh Bean, stood in line with me for Milstein’s autograph. He went up to the great violinist and said “Maestro thank you so much for still playing like this.” Now that got a tear or two. You can see Milstein’s autographed program book in my office at NEC.

Federico Garcia Lorca, the great Spanish poet and writer, produced an essay in the 1930’s about “this mysterious force, that everyone feels and no philosopher has explained” that is, “in sum, the spirit of the earth.” He called that force “the Duende,” and described a flamenco singer who had moved him enormously with her duende.

“Then the “Girl with the Combs” got up like a woman possessed, her face blasted like a medieval mourner, tossed off a great glass of Cazalla at a single draught, like a potion of fire, and settled down to singing – without a voice, without breath, without nuance, throat aflame – but with duende! She had contrived to annihilate all that was nonessential in song and make way for an angry and incandescent Duende, friend of sand- laden winds, so that everyone listening tore at his clothing almost in the same rhythm with which the West Indian negroes in their rites rend away their clothes, huddled in heaps before the image of Saint Barbara.

The “Girl with the Combs” had to mangle her voice because she knew there were discriminating folk about who asked not for form, but for the marrow of form – pure music spare enough to keep itself in the air. She had to deny her faculties and her security; that is to say, to turn out her Muse and keep vulnerable, so that her Duende might come and vouchsafe the hand-to-hand struggle. And then how she sang! Her voice feinted no longer; it jetted up like blood, ennobled by sorrow and sincerity, it opened up like ten fingers of a hand around the nailed feet of a Christ by Juan de Juni – tempestuous!“

That it exactly what I was privileged to hear with these great artists at the end of their long careers when they had given us so much and still wanted to give even more.

![]()

Leave a Comment: