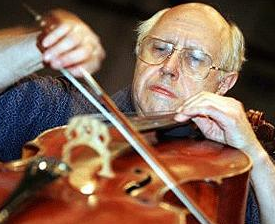

Rostropovich: The Musical Life of the Great Cellist, Teacher and Legend, by Elizabeth Wilson

Editor's Abstract

Editor's Abstract

Since I do lot of teaching I read a lot of books. Not all of them are music-related, but a high proportion of them are. From time to time in this space I’ll be posting reviews of books I’ve read, with the hope that 1) you’ll be able to sort through books more quickly (as to whether you really want to spend the time reading them) and 2) you’ll read something that you might not have otherwise considered. Enjoy!

Yvonne Caruthers

Saddened by the loss of Mstislav Rostropovich in April 2007, I looked forward to reading this book, written by one of Slava’s former students in Moscow (who now resides in Italy). Ms. Wilson writes lovingly about Slava, as only a student can. She regales us with story after story about what it was like to experience the man’s genius at close quarters.

The book opens with biographical information about Slava’s early years: studies with his father, surviving World War II, moving to Moscow, and his years at the conservatory (where he was soon recognized as being world-class talent). Most of this section can be found other places since the facts of Slava’s life have been often written about.

What makes this book a treasure is the inside information that Ms. Wilson gives us when she writes about “Class 19,” Slava’s cello class at the Moscow Conservatory. This illustrious class included many of today’s notable performers: Karine Georgian, Boris Pergamenshikov, Jacqueline Du Pré, David Geringas, Mischa Maisky….the list is long. (The complete list is found in Appendix 1.) They learned together, competed with each other, and soaked up whatever they could from Slava. It must have been a heady experience, full of highs and lows, and those feelings come through beautifully in Ms. Wilson’s lucid prose.

Interspersed with Ms. Wilson’s accounts of Slava’s early performing career and highlights of his teaching are first-person accounts by a few of his other students. The one I found most riveting is the one by Victoria Yagling, who chronicles Slava’s fall from grace with the Soviet authorities of the time for the “sin” of befriending Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Parts of it are downright hair-raising. Such passages elevate this book from being “another biography” to being a powerful historical document. (Appendix 2 is the letter Rostropovich wrote to the authorities defending his action of allowing Solzhenitsyn to live at his (Slava’s) dacha).

However, it’s at this point in Slava’s life (1974) that the book ends. A more apt sub-title for Ms. Wilson’s book might be The Early Years, since the book doesn’t cover his entire musical life. Slava’s wife, the eminent (and still teaching) Russian soprano, Galina Vishnevskaya, wrote her autobiography “Galina” in 1984, ten years after their forced exit from Russia. I asked her in 1990 if she’d ever write about what had happened to them after they left the Soviet Union. She smiled wryly and said “perhaps one day.”

Ms. Wilson’s epilogue gives the barest facts of Slava’s years in the west and his return to Russia in 1990. Volumes could be written about those years: the immense project of recording the complete symphonies of Shostakovich; the marathon of concerts he played for his 60th birthday, in cities around the globe, showcasing virtually every major piece written for the cello (mostly from memory); his humanitarian efforts once Russia welcomed him home – the list of post-1974 achievements is long and deserves more than passing mention.

To quote Slava’s wife again: “Perhaps one day.”

Leave a Comment: