Connecting Curriculum: Rethinking the Design and Scope of Outreach Education Programs

Editor's Abstract

Editor's Abstract

In the article below, New Bedford Symphony Orchestra Education Director Terry Wolkowicz summarizes the yearlong educational program that was undertaken by the NBSO this year. The orchestra’s innovative education program aimed to go beyond simply presenting children’s concerts of classical music, and to integrate classical music within the academic curriculum – creating synergies and connections for students and teachers. It sounds like it was a great success!

What role can an orchestra play in a child’s education? Most education outreach programs today consist of in-school performances or Young People’s Concerts aimed at bringing the excitement, joy and enrichment of classical music into the lives of children. While these types of programs provide meaningful and engaging experiences for children, there is an even greater opportunity for orchestras to impact children’s lives through programs that utilize a unified, concept-based curriculum that integrates the musical experience only an orchestra can provide with key learning elements from other academic disciplines. This approach produces outstanding results for student learning, yielding substantial, measurable improvement in both musical perception skills and core academic achievement.

With the introduction of the Common Core State Standards, schools are now shifting their focus to explore a smaller range of topics at a deeper level, requiring students to use higher-order thinking skills that include evaluating, synthesizing and analyzing information, topics and ideas. Teachers are aiming to move beyond countless, isolated facts and instead build more coherent, comprehensive and connected understandings.

Over the course of the past four years, the New Bedford Symphony Orchestra has also realigned the focus and mission of their education programs to reflect this model of connectivity and depth of understanding. While we have continued to use standard outreach models such as in-school performance programs and Young People’s Concerts, we have transformed those programs by completely redesigning them from the basis of a unified, concept-based curricular approach, which includes classroom visits by education staff members as a means to more closely partner with classroom and fine arts teachers. This has created opportunities for our organization to collaborate with schools in ways that seamlessly connect classical music to the everyday education of children, while at the same time redefining the role of the orchestra as a close, familiar and essential partner with our schools, principals, classroom and fine arts teachers, and students.

In this article, we will show how a connected, concept-based curriculum that united several normally distinct educational outreach programs served to integrate classical music into schoolchildren’s everyday lives and learning activities. This has also created a broader base of new advocates within the schools who request, promote and actively engage in our programming.

What makes this approach unique is that each year, the NBSO selects a concept of study that is authentic and relevant to classical music. This concept is then explored over the course of an entire school year and carried across several of the NBSO’s education outreach programs. During this past year, the concept of study was symmetry. Over the course of this year, our programs explored symmetry in classical music, art, nature and geometry.

We began our program in the fall, presenting the in-school performance program, The Sounds and Shapes of Symmetry in over 50 area elementary schools. A trio of NBSO musicians visited these schools with the NBSO Education Director and performed a lively, interactive concert program for students in grades two through five that demonstrated the ways in which composers create and use symmetry in classical music.

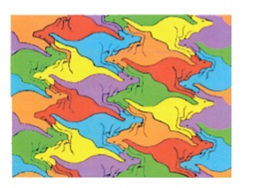

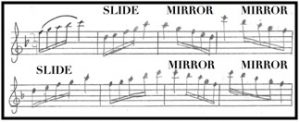

In one example, the musicians demonstrated mirror symmetry by performing the trio from Haydn’s Symphony No. 47, where Haydn composes melodies forward and then repeats them in retrograde. The students then saw a visual representation of mirror symmetry in a print by M.C. Escher entitled Day and Night. In his print, the symmetrical black and white geese fly in opposite directions creating mirror symmetry.

The students then used a giant “Escher Sketch” to demonstrate mirror symmetry as they arranged large, colorful fish magnets in a display on the large magnetic board.

Throughout the program, students’ exploration of slide (translation), mirror (horizontal reflection) and flip symmetry (vertical reflection) flowed freely, cycling from classical music to art to geometry. As this coordination among classical music and other subject areas continued, the lines between each discipline began to fade as the concept of symmetry was authentically and equally represented in each. This connection helped the students to build a deeper and more flexible understanding of symmetry, potentially far greater than could have been possible from exposure to one subject alone. At the end of the program, the musicians inducted the children into a “top secret” organization called the S.D.A. (Symmetry Detection Agency) formed by the NBSO. As agents in the S.D.A., over 8,000 students took an oath of service to explore symmetry in their environment and to search for, and create symmetry evidence in music, art and photography. All S.D.A. agents received their special agent ID badges and learned the secret hand sign for the agency.

In the following months, these students received a second visit from an NBSO education staff member, this time in their own classroom. During these classroom visits, the students, or S.D.A. agents, shared symmetry evidence they had discovered, and explored some new ones, as well. In some classes, students would point out symmetry evidence in the architecture of their school building.

Other classes had fun creating symmetry statues with classmates, posing in ways that demonstrated mirror or slide symmetry. On many occasions, students manipulated classroom objects or building blocks to show symmetry, while other students created original symmetrical artwork.

Students also composed and performed melodies or rhythms that demonstrated slide (sequence), mirror (retrograde) or flip (inversion) symmetry. On many occasions, the students used xylophones or glockenspiels to perform their symmetrical melodies. The students would compose and perform these melodies and then quiz their classmates to identify the specific type of symmetry they had used.

Overall, these classroom visits provided a unique opportunity to partner closely with the classroom teachers and their students. In the smaller setting, students were free to share and create, improvise and explore. From the perspective of the classroom teachers, many were excited and extremely appreciative of the opportunity to reinforce the concept of symmetry while witnessing new creative contexts and applications happening right within their own classroom. Following a visit, one teacher remarked to her principal, “This was the most valuable 30 minutes this year!” Another teacher requested, “Can you come back tomorrow … or everyday?” Here again, there was seamless, fluid exploration among different disciplines all authentically connected by a common, shared concept.

To these children, classical music was as much a key component to their learning experiences as reading and math. The music was not viewed as foreign or outside of the realm of learning. To them, it was completely natural to explore a concept by seeing it, building it, and hearing it through classical music. While in the classroom, we were able to build a bridge that connected events on our concert stage directly to the students and their teachers, as we had an opportunity to connect and explore the concept of study with them on their home turf.

The year’s exploration culminated at the NBSO’s annual series of Young People’s Concerts with a program called “The Agents of the S.D.A.” As we gathered our S.D.A. agents in our concert hall, they experienced symmetry again, but now with the power and excitement of a live performance with the full NBSO. Students were thrilled to hear the orchestra demonstrate the concept of symmetry through performances works by Vivaldi, Beethoven, Haydn, Tchaikovsky, Shostakovich and Liadov.

Photo courtesy of John Sladewski/Standard-Times.

Students react during the 2014 Young People’s Concerts, “The Agents of the S.D.A.”

Throughout the concert, video segments featuring selected work by our S.D.A. agents were incorporated into an accompanying power point presentation on a large screen suspended above the orchestra. In video interviews, our agents were shown sharing their discoveries about symmetry through photographic evidence, original artwork, musical compositions and performances, symmetry statues, and a special symmetry dance party. The children were delighted to see their work shared with the entire audience. One student said, “Thank you for showing my artwork in the concert.”

From the perspective of our musicians, the Young People’s Concerts were a distinct departure from the norm for an educational concert experience. Since our organization had already personally connected with these children during two in-school programs prior to the concert, the children displayed a sense of familiarity and engagement not before experienced. Before each concert, musicians walked up and down the aisles engaging children in conversation and answering questions. The children were quick to shake hands, wave and do the S.D.A. secret hand sign. One student wrote the orchestra saying, “I liked seeing Randolph, Peter and Emmy again, walking through all the people at the beginning of the concert.” The content and curricular preparation enabled all of our attendees to feel more connected to the musicians and prepared for the entire concert experience.

This year, the NBSO took an extra step to pre-test and post-test four schools who had participated in all aspects of the symmetry program. These assessments offered a clearer picture as to the quality and level of impact that these programs had on the students.

In the beginning of the school year, prior to the first in-school music program, second and third grade students were given a test that assessed their symmetry understanding in math, visual perception, auditory perception and the ability to create and describe symmetry through written narratives. Following the Young People’s Concerts, we returned to give the same test again to the same students.

Example 1b

Post-test example:

My pepperoni pizza’s symmetrical because in the middle I made a line and at the top I put two triangles that are facing up and two triangles that are facing down.

In the math section of the test, students were asked to create mirror symmetry and identify slide, mirror and flip symmetry. The pre-test scores for the four schools combined showed an accuracy rate of 70%. Following the NBSO’s symmetry program, these same students improved to 97% accuracy on the same math section. In an inner-city school with a low income population, these math results were even more impressive, with students improving from 54% accuracy to 94% accuracy during the post-test.

On one section of the test, students were asked to create a symmetrical pattern by drawing pepperoni pieces on a cheese pizza. The post-test scores from four schools combined showed an improvement from 24% accuracy to 71% accuracy. In the illustration, comparisons can be made between the pre- and post-test of one student’s pepperoni pizzas. Following the arrangement of pepperoni, students were asked to describe the pizza and they ways in which they had created a symmetrical design. In illustration 1a and 1b, a student’s ability to describe symmetry improved along with her ability to represent the symmetrical design on the pizza.

pre-test example:

I see all different colored kangaroos.

post-test example:

They are symmetrical because the kangaroos are all the same size same shape and same measurement. The kangaroo picture is flip symmetry.

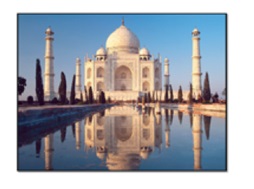

In both the pre- and post-test, students were given visual examples that included a tessellation of kangaroos and an image of the Taj Mahal. In both examples, students were asked to describe how these images related to symmetry. On the test scores, the students’ ability to analyze, describe and write about symmetry in artwork and photography improved by 66%, increasing from 21% to 87%. The improvement was even more pronounced with the above mentioned inner-city school, with improvement from 5% to 89% in the students’ ability to describe and write narratives about symmetrical images.

In the aural component of the symmetry assessment, students heard two melodies performed live. They were asked to determine whether these melodies were symmetrical or not symmetrical. If the melodies were an exact repetition or maintained the same contour and rhythm starting on higher or lower pitches, then the students could identify that they were symmetrical. However, if the melodies did not maintain the same contour and rhythmic pattern, the melodies would be marked as not symmetrical. The post-test assessment showed that students from all four schools improved in the aural component from 39% accuracy in the pre-test to 84% accuracy during post-testing.

pre-test example:

I see a big tower.

post-test example:

I see flip when the building is reflecting off of the water also the big poles, people, tree and sky. I also see mirror because if you split the picture in half most everything will mirror off each other.

Overall, student scores on the assessment improved from 39% accuracy to 84% accuracy at the completion of the symmetry program. While accuracy scores show a significant improvement throughout all four schools, the excitement and engagement of the students while taking the test also improved. During the post-test, students were eager to share and respond. They took more time and wrote at greater length and detail about the symmetry images. Narratives that began the year in a single sentence where expanded to a paragraph and more on the post-test. Students became better able to search for symmetry evidence and represent that information through written narratives with greater detail, articulation and vocabulary.

These assessment results provide strong support for the value and importance of music education in children’s day to day learning. However, most traditional orchestra educational models have focused exclusively on exploring concepts and sharing information within the discipline of classical music, and question the need or the validity of including other subject areas outside of music in their educational outreach programs. This view assumes that the inclusion of outside connecting subjects take something away from the musical learning experience.

Over the course of this year, we have witnessed the opposite. The connection of symmetry to art and math resulted in building a greater understanding of symmetry in classical music. This can also be said to work in the other direction, and that by exploring symmetry in classical music, students gained a greater understanding of symmetry in art and math. Indeed, the overall experience of connection-making speaks to the very basic ways in which we learn and make sense of the world around us. From the perspective of a music organization, we make no compromise in the quality and integrity of our goals as musical educators. At the same time, we need to recognize that we have the ability to achieve so much more by exploring musical concepts alongside other relevant disciplines.

As mentioned earlier, the additional interactions with students and extended exploration of symmetry across the school year created a closer alignment with principles embedded in the Common Core State Standards. Currently, principals and teachers are actively looking for programming that extends the learning experiences beyond the one field trip or in-school performance. Many have articulated that, “the days of one-and-done field trips are over.” In order to support deeper engagement and learning, schools are requiring that partnering organizations offer multiple opportunities to explore content or topics at a greater depth of study.

Another benefit arose unexpectedly this year, which involved the ways in which our educational programs were perceived, integrated and valued by the schools. Apart from music teachers, who continue to be our greatest advocates, classroom teachers and principals became new and strong advocates for our programming. One classroom teacher remarked, “the interactions with members of the symphony throughout the year has sparked an interest in their learning and appreciation for classical music.” These additional supporters helped to facilitate the numerous encounters with their students throughout the school year. With this added time, our organization, and classical music, found its way to the center of instruction and learning and thereby established a strong, present and relevant role in the schools and with the children of our community.

Leave a Comment: