Body Mapping: What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body

Editor's Abstract

Editor's Abstract

My college friend and ROPA colleague, Sherill Roberts, has been telling me about Barbara Conable for many years. Sherill is a cellist who had to overcome some pretty serious health issues in her past, and thus she is particularly attuned to the needs of her body in terms of movement. She recently became certified to teach the Andover Educator Body Mapping course, and suggested that I contact Amy Likar, who has taken over as the group leader now that Barbara Conable has semi-retired.

Amy explains what Body Mapping is and how it can help your playing, and then presents a fascinating and inspiring interview she conducted with Barbara.

Ann Drinan

As a performer with injury, I was very lucky as a university student. When I mentioned to my teacher some pain I was having, I was advised to take an Alexander Technique class. The class was a revelation to me, not only because I was learning how to play pain free, but because I was able to play with the tone and the concept of sound I had always had in my mind but could never achieve consistently. The foundation for my Alexander Technique study was something my teachers, Barbara Conable and William Conable, called Body Mapping. Learning how to move more efficiently based on a corrected and refined body map allowed me both to play for long periods pain free and to achieve more musically-consistent results.

Barbara and Bill had been working with the concepts of Body Mapping since the mid 1970s, though the concepts had been implicit in the earlier dense writings of F.M. Alexander. The Conables made them explicit and wrote of them in simpler language.

Dancers learn kinesiology and fitness professionals learn exercise physiology, but musicians have had no equivalent training until recently. Musicians had instead relied on teaching traditions passed down from generation to generation that were not always based on accurate information about how the body is actually designed and efficiently used. Fortunately, organizations like the Performing Arts Medicine Association are changing this by hosting annual symposiums and sponsoring conferences concerning the health and well-being of musicians.

Barbara Conable decided to bring basic anatomical information into a single course called What Every Musician Needs to Know about the Body, with a text by the same name. In the late 90s, she formed Andover Educators to train musicians themselves to teach the course and bring them together into a network for the benefit of the rest of the musical community. The goal of the network is to put music education on a secure somatic foundation. Given the discoveries concerning the body map that have come out in neuroscience in the past few decades, we can now add music training on a secure neurophysiological foundation.

Your body map is your self-representation in your brain of your own body – how you think it is and how you think you move. Body Mapping is the conscious correction and refinement of your body map. If your map is accurate, you don’t have a problem because you already move well, but if it’s a bit off or totally off, you can have pain and potentially face the end of your career from injury caused by the faulty map. Of course, a thorough medical check up with a physician is always necessary to rule out disease. But if yours is a problem of misuse, overuse and abuse, you must gain a clear understanding of how the body was designed and made to work as a whole to create music. Then as artists, we can make musical choices based on movement choices that work well with the design of our bodies rather than against them, and we can make movement choices that enhance our music making rather than limit it. Thus the information that permits us to move more easily also freely enhances our performance. Having a basic understanding about the body in movement can also clarify movement choices for us when we are in more stressful situations, helping us recover more easily when we are more apt to feel tense.

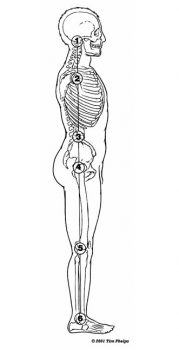

The foundation of Body Mapping is understanding how weight delivery and balance work throughout the body. It is through the genuine understanding of weight delivery and balance that free breathing, and free use of the arms and legs, can occur. When we play, well we play with our whole bodies, which are supported and organized centrally around our spines. We may perceive balance and poise around our spines using our lively, on-going body awareness. Within our bodies we may feel:

- 1. the balance of our heads on our spines, at the center,

- 2. the balance of our arm structures over our spines, at the center,

- 3. the balance of our thorax on our massive lumbar vertebrae, at the center,

- 4. the balance of our upper half over our legs, at the center,

- 5. the balance at our knees, at the center, and

- 6. the balance of our bodies on the arches of our feet, at the center.

As we work on our body maps, we are working by means of practical anatomy specifically on the quality of movement and its perception. We musicians move for decades to play, sing, and conduct, so we need to know that we can choose movements that distribute effort throughout the whole body to achieve free, easy music making rather than isolating effort in a single part. We secure wholeness and ease by an accurate and adequate body map.

We need to include in our body maps all our relevant senses: seeing, hearing, touching, and kinesthesia, the sense of movement. Musicians constantly use the sense of vision to watch the conductor and look at the music on the stand, and we use peripheral vision to see colleagues. We constantly use our hearing to sense how our part fits into the greater whole; we listen to hear our tone or hear if we are playing in tune or dynamically appropriately for a passage or a venue. We use our sense of touch to know which keys or valves or strings we are depressing from passage to passage, and how much pressure we feel on the skin. We must also include the quality of our movement and acknowledge that we make an infinite number of movement choices throughout a practice session, rehearsal or a concert. Some musicians also speak of how the air they breathe tastes or how the room they are performing in smells. Full sensory information and feedback is vitally important to the choices we must make as musicians.

Then, most importantly, we have our inclusive attention or awareness – or the contents of our consciousness and what we want to include and what we can choose to leave out. Symphonic musicians are subjected to many stimuli in each moment. We use our awareness to choose our actions and reactions – our movements, our thoughts and emotions. We need to know that physical, mental and emotional awareness work together and affect each other as we work as artists. Many musicians commonly leave their bodies out of their awareness until pain becomes too severe to ignore. Our awareness allows us to notice how we react to these different stimuli, and the clarity of having an accurate, adequate body map and self map allows us to recover physically as well as mentally and therefore easily keep musical intention as our focus while performing.

I did an informal anonymous survey of my symphony colleagues on what they see as some of the main issues they face on the job. Based on the issues my colleagues raised, I corresponded with Barbara Conable for her insights and thoughts, given that she has worked with musicians for over 30 years.

[AL] How do you see Body Mapping and inclusive awareness as a remedy for the problems symphony musicians face?

[BC] Inclusive awareness is a part of Body Mapping because how a musician uses attention is the direct result of how attention is mapped. When, for instance, musicians fail to map kinesthesia as essential to playing, they ignore their sensations of movement and thereby lose their second greatest resource, next to their ears, for knowing what they are doing and improving it. The only remedy for this loss is to map themselves as having six senses, including one that gives them vital information about where they are moving and how. Then they will value and train their kinesthesia with the same dedication they bring to their ear training. The great musicians just do this naturally. They feel their movement and monitor it for freedom just the way they monitor their sound for intonation, but less fortunate musicians have to consciously learn to do this.

Many musicians are profoundly harmed by habits of concentration. They narrow attention just when they should be expanding and organizing it. Musicians must attend to many things at once, just as basketball players do when they give proper inclusive attention to the whole court, the ball, their own moving, their teammates, their opponents, the fans. Everyone knows that basketball players must do this, but musicians are sometimes overwhelmed by what they must become capable of attending to: the whole orchestra, the conductor, the notation, their own instrument, their own moving, their intonation, the audience. At any given moment, if the musician is using attention correctly, all this will organize concentrically, with that which is in focus at the center of awareness, and that which is in the periphery nearer or farther away from focus depending on its importance, just as it does for a basketball player. Body Mapping aids the musician by getting all the senses mapped, including kinesthesia, by cultivating the wholeness and fluidity of awareness, and by securing an accurate and adequate map of the structure, function, and size of the body so that when musicians are in rehearsal and performance their body maps dictate the quality of their movement free of error or omission without their having to think about it. Injured musicians almost always leave out kinesthesia when mapping senses.

[AL] How many symphonic musicians have you worked with over the years and what were the main issues you saw facing symphonic musicians?

[BC] I taught countless musicians, it seems to me, looking back, but I’ll try to count. I’ve had dozens of symphony musicians as long-term, weekly students. Others have come to my summer courses. Sometimes I have done workshops for whole orchestras, especially those in the pits of touring shows. I have worked with student orchestras in university residencies. Symphony musicians frequently attend the conventions for their own instruments, and I taught those conventions over many years. The problems symphony musicians face are the ones you ask about in this article, but the one that mainly concerned me was muscular tension. Muscular tension itself is painful, and it causes injury and a loss of facility and musicality. Muscular tension can be a response to the kinds of pressures you name in your article, but it is more often a product of a faulty body map, which is why developing an accurate and adequate body map is so important. An accurate and adequate body map insures muscular freedom, and muscular freedom promotes technical facility and increased musicality. Many musicians mistakenly confuse tension and intensity, tensing their muscles to try to create a big sound or the requisite emotion. This never works. They must learn to keep their bodies free of tension in order to freely produce the sound they want with whatever emotional intensity is required. The intensity is in the sound, not in the musician’s body.

[AL] In thinking of our experiences, I and my colleagues raise the following issues:

1) Negative internal dialogue or self talk.

[BC] Musicians vulnerable to inner dialogue are those whose body awareness is diminished or absent. When their hearing and seeing becomes profoundly grounded in a secure and on-going perception of the body, especially of movement, their inner voices are quieted, so that’s where the remedy begins but not where the remedy ends. Their kinesthesia must then integrate with their other senses into an inclusive awareness of real integrity and fluidity.

Also, the musician’s self map must change. The self map is part of the body map and is linked to language so that much of a musician’s self-map is revealed in the self-talk itself and may include words you wouldn’t like to see in print. A musician vulnerable to negative self-talk must cultivate a self map as follows: I am an artist; I am a musician; I am a trombonist. An artist is one “who produces or expresses what is beautiful, appealing, and of more than ordinary significance,” according to The American College Dictionary. A symphony musician securely mapped as an artist is too busy with the task of producing and expressing what is beautiful, appealing, and of more than ordinary significance, as symphony music certainly is, to talk trash to its producer and expressor. A person securely mapped as a musician in a world-wide community of musicians will talk to himself or herself with respect and compassion, with respect for the importance of the work and compassion for its difficulty. Supportive and encouraging self-talk will occur during practicing, but it will fall away for the most part during rehearsal and performance because it will have done its work in practicing. A musician securely mapped as a trombonist (or whatever, of course) will assume a status commensurate with that of the instrument. A musician with a deep regard for the trombone can thereby learn a deep regard for its player.

Music itself is a musician’s greatest resource in eliminating negative internal dialogue and in confining positive internal dialogue to those moments in practicing when it is useful. Resolutely turn your ears to the music and the music will draw your attention and hold your attention. Since music is a language of its own, it will gently push spoken language into the arenas proper to it and out of the mental territory ruled by music.

2) Too many services in one day or one week without enough time off to recuperate/unpredictable scheduling.

[BC] A long-term solution will involve aggressive advocacy, resolute non-stop education of symphony management and of boards of directors about what is actually involved in the symphony musician’s job, a greater self-valuing on the part of the musicians themselves, and a demand on the part of audiences for more expressive and collaborative musicianship. In the meantime, musicians must acknowledge at every moment that they are under terrible pressure and are radically overworked. Unless they acknowledge the reality, they cannot deal with it. I am old enough to remember when symphony musicians worked a sensible amount, with leisure to practice fully, to play chamber music, to enjoy their families, to care for their instruments, to cultivate friendships, to renew their spirits, so I know better than many current musicians how much they have lost. Musicians must in the meantime use every possible resource to stay healthy, so an adequate and accurate body map is essential, as is a high level of self-care.

Most important is to learn highly effective and efficient practicing, which involves staying wide awake to movement, becoming very astute at analyzing and changing movement, gaining a profound sense of the deep structure of the music so that each note makes sense in relation to the whole piece, and keeping the emotional content of the music front and center. Symphony musicians are susceptible to ignoring the emotion and therefore practicing loses its appeal and becomes a miserable business of learning notes. This must be avoided and reversed.

3) The challenge of being an emotionally expressive musician over and over again to the point where the job feels like skilled labor rather than expressive musicianship.

[BC] This is a biggie and it is made worse by the simple fact that some symphony conductors do in fact regard “their” musicians as skilled labor whose only task is to express the conductor’s interpretation of the emotion of the music with the sound and tempo the conductor chooses. Musicians playing under such a conductor will have to constantly feel and express the frustration of their situation and seek other opportunities to be full-blown musicians. These musicians will sometimes blessedly experience guest conductors who are collaborative, who value them and listen for their expressiveness in order to enhance it, who listen for just the sound this group of musicians can make and do everything they can to showcase just that sound, who are constantly listening to the musicians to see what these musicians know about the music that they do not, so that every rehearsal is an opportunity to learn and make the interpretation even more sophisticated and complete. Symphony musicians must cling to those moments with collaborative guest conductors and always remember that that’s how it is supposed to be.

4) Not really knowing if I am working too hard until it’s too late, and the aches and pains find their way back.

[BC] The only answer to this is inclusive attention so secure that one knows in the moment that one is working too hard. This is just like knowing that one is playing out of tune. Playing out of tune is perceived by the auditory sense; working too hard is perceived by the kinesthetic sense and by the tactile sense, feeling too much pressure on the finger, for instance. There is another important similarity. The musician who plays in tune is the one who is always listening for intonation and notices when good intonation is absent and makes corrections accordingly. The musician who never works too hard is “listening” kinesthetically for freedom and appropriate work and notices its absence and corrects back to freedom.

5) Lack of adequate preparation time for more difficult scores.

[BC] Even under these difficult conditions, some musicians are learning the difficult scores in time, which, of course, only makes the lives of those who aren’t more difficult. My observation is that those who learn the scores do so by constant attention to deep structure in the music, constant attention to the emotion of the music, constant attention to their own movement so that they can steadily push it toward as much efficiency, freedom and ease as possible. These musicians never just learn the score; they always have loftier goals, even under time pressure. They are always learning about the music, about emotion and meaning, about movement, and about themselves. These loftier goals feed the more mundane goal of getting the notes. Also, these musicians take frequent breaks, if only little ones. They give their brains genuine rest to assimilate what has been attended to. They also keep their own emotions vivid in their experience. They never waste any energy trying not to be frustrated or angry or annoyed or impatient or whatever they happen to feel at the moment. They never concentrate but always let their awareness play, hearing the birds sing, for instance, while they hear and feel their own practicing. Concentration is exhausting, but an inclusive awareness is constantly refreshed by its variety and fluidity.

6) Commute time for people who have to drive long distances to jobs or play “Freeway Philharmonic” jobs.

[BC] These musicians must learn to drive with physical freedom and inclusive attention so that they are practicing in driving what they will do when playing. They can listen as they drive to books about the Alexander Technique and Body Mapping so that they are improving their body maps as they drive. They can listen to the music they will be playing so that they have another way to secure the notes and learn the emotion and structure of the music. They can use every moment stopped in traffic or at traffic lights to palpate their hands and refine their body maps of their hand bones and joints. They can work on the quality of their breathing as they drive. They can sing.

7) Terrible chairs that make it difficult to sit well for long periods of time.

[BC] I know musicians who carry their own chair into as many circumstances as possible. Others carry cushions or foam wedges to modify bad chairs. In every case, a musician needs to have a good look at a chair and determine what is the best use of it, whether to lean back in it or to sit forward of the back, where the musician\’s legs should best be, and where on the seat to sit. Find in any chair as much variety as possible in sitting so that the requirements on the body are constantly changing.

8) Inability to leave work (rehearsals, performances) behind at “the office.”

[BC] This is often because something about the rehearsal or the performance has not been acknowledged or expressed. The musician will need to feel fully whatever the reality is, whether disappointment or humiliation or frustration or pride. Then the feeling will need to be expressed appropriately, whether verbally or in improvisation on the instrument or in pounding something soft. If the feeling that is keeping a musician locked into “the office” is disappointment in one’s own performance, then the musician must express clearly what was disappointing and then resolutely address the inadequacies in practice so that real learning occurs. Then the past can be left in the past because the future is brighter.

9) The conundrum of the musician “feast or famine” – the fear of turning down work and then not being called again.

[BC] Musicians must always state very clearly, when they turn down work, WHY they are turning down work. They must state that they are already employed during that time and that they want to be called again in the future. This would seem to go without saying, but I have heard musicians with my own ears turn down work without saying why and without inviting calls in the future, so I know it needs to be said. Musicians should take the further step of saying when their current gig is over and of giving a call to the contractor to say they are now once again available. I’m not advocating nagging, of course, just the straightforward offering of information.

Musicians need to constantly remind contractors of human limitation. Don’t be afraid to say, “I’d just love to take your job, but if I do I won’t be able to do the one I have as well as I expect of myself.” Contractors will be assured that you will give the same priority to their job next time.

Leave a Comment: