Benjamin Franklin, the Composer

Editor's Abstract

Editor's Abstract

Michael is Music Director of the Waltham Philharmonic Orchestra and Sharon Community Chamber Orchestra in Massachusetts. He regularly teaches young students in orchestral settings and conducts Oliver Ames High School orchestras in Easton and Sharon Community Chamber Youth Orchestra. Since moving to the United States Michael performed with the Alabama Symphony, Boston Lyric Opera, and Boston Classical Orchestra. Michael Korn has appeared as a soloist with orchestras throughout the former Soviet Union, in Israel, Europe, Africa, and the US. He also founded the critically-acclaimed Chagall Trio, “String Summit,” the first chamber music festival for youth in Alabama, and now is organizing a new chamber music festival in Easton, Massachusetts.

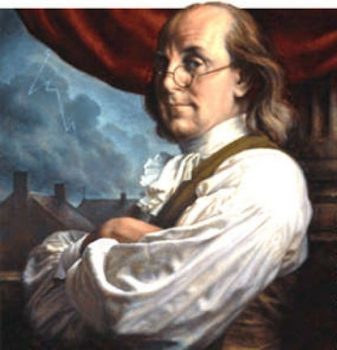

As we turn to our Founding Fathers, we assume to find ourselves in the world of politics, domestic and foreign state affairs, economy, law and philosophy. Indeed, many of the statesmen studied ”politics and war”[1] during the formative years of this country. Yet, a few pursued a lifelong interest in music. Thus, Thomas Jefferson’s musical erudition, as well as Francis Hopkinson’s contributions to music, are well documented. Benjamin Franklin, perhaps the most recognized American polymath, also participated in the music domain during his lifetime and, in addition to the knowledge of several instruments and commentaries on music theory, left a legacy as an instrument maker and a composer. Noteworthy is Franklin’s involvement in promoting the music of two of the first American composers, Hopkinson and Antes, which can be traced through his letters.

In this essay I would like to discuss Franklin’s musical heritage as a composer. By any means, he was not a prolific composer, nor are his compositions considered to be jewels of repertoire but they certainly exhibit historical and musicological value. Franklin wrote his first known composition as a young teenager. The ballade, which appeared in 1719 and later was characterized by himself as “wretched stuff,” was based on the dramatic events connected to the death of the notorious pirate Edward Teach (a/k/a “Blackbeard”). In ten stanzas of “The Downfall of Piracy” Franklin describes in a youthful and romanticized fashion the violent end of Blackbeard and his crew.[2] In essence a drinking song, it was fitted to a tune well known at the time, “What is greater joy and pleasure,” and became a testament to Franklin’s daring nature. His musical inclinations, though, were bitterly dismissed by Franklin’s father as “beggars” business. Although Franklin’s authorship of the ballade is challenged by some scholars, Leonard points to the historic evidence leading us to believe in the authenticity of the composer’s “Opus 1.”[3]

Either due to the discouraging comments of the old soap maker or demands of all sorts throughout the American celebrity’s life, at least six decades separate Franklin’s first and second and, in fact, final work. Nonetheless, it is important to note that during these years, Franklin did not abandon his musical enterprise. Franklin’s own notes, as well as the accounts of his correspondents, indicate that despite his knowledge of the old masters such as Corelli, Geminiani, and Handel, as well as contemporary composers, at least due to his acquaintance with Madam Brillon, he preferred “plain old Scottish song” to “mere compositions or tricks.” Not surprisingly, Franklin engaged his modest harp, guitar, and violin skills during his performing career in the former genre, and most famously expressed his egalitarian views on music theory with quite disparaging criticism of classical music in the 1761 letter to his brother Peter.[4] Shortly after, in January of 1762, the Bristol Gazette announced one of the most lasting and influential of Franklin’s musical inventions, the glass armonica. The newly-constructed instrument allowed for chord production unavailable in the previous versions of glass armonica and, as the result of these modifications along with its celestial tone, became a very popular attribute on the musical scene of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Nevertheless, it is in Paris, where Franklin served as the United States Minister to France from 1778-1885, that he wrote his string quartet, which was discovered in 1941 by G. de Van in the annals of Bibliotheque Nationale and published five years later. The musicological uniqueness of this piece is three-fold. First, as the standard string quartet instrumentation of this period calls for two violins, viola and cello, Franklin’s piece[5] was scored for three violins and cello. Another special characteristic is the composer’s choice of a suite-like (Introduction, Minuet, Capriccio, Minuet, and Siciliano) outline rather than, typical for this genre, a four-movement structure. The third property, however, shows Franklin’s compositional approach in the most scientific manner as he features scordatura applied to every string of each instrument, allowing the entire piece to be played on open strings without any fingering and, thus, making it accessible to musicians with minimal skills.

Nevertheless, it is in Paris, where Franklin served as the United States Minister to France from 1778-1885, that he wrote his string quartet, which was discovered in 1941 by G. de Van in the annals of Bibliotheque Nationale and published five years later. The musicological uniqueness of this piece is three-fold. First, as the standard string quartet instrumentation of this period calls for two violins, viola and cello, Franklin’s piece[5] was scored for three violins and cello. Another special characteristic is the composer’s choice of a suite-like (Introduction, Minuet, Capriccio, Minuet, and Siciliano) outline rather than, typical for this genre, a four-movement structure. The third property, however, shows Franklin’s compositional approach in the most scientific manner as he features scordatura applied to every string of each instrument, allowing the entire piece to be played on open strings without any fingering and, thus, making it accessible to musicians with minimal skills.

As six more manuscripts under different names with various combinations of the movements were consequently discovered in several European libraries, Franklin’s authorship of the quartet became the subject of dispute between music historians. For example, Marrocco suggests that among available composers-candidates (Haydn, Pleyel, Ferrandini, and Franklin), Franklin may have composed the score based on his mathematical abilities; he also took into consideration the overall dilettante level of the piece. Yet he suggests that, due to a number of specifics in the manuscripts that were found in Vienna and Prague, Ferrandini is the most likely composer. Interestingly, at the same time, Marrocco implies that writing such an amateur piece would, perhaps, destroy the reputation of Ferrandini, a professional composer and court musician in Munich.[6]

Conversely, Grenander also acknowledges Franklin’s scientific habit and rational calculations in order to simplify the performance, but he finds these factors sufficient evidence to determine his rights on the piece. In addition, Grenander suggests that Franklin’s “common humanity” aesthetics, as well as his social interactions in the salons of Madam Brillon and Madam Helvetius, fueled the quartet’s composition. Both ladies, famous Parisian socialites, hosted chamber music gatherings and became an influential source of Franklin’s attraction to the pleasures of life. As Franklin’s relationship with Madam Helvetius culminated in his marriage proposal and likely, in the scholar’s opinion, could spark Franklin’s desire to flash his abilities, Madam Brillon’s friendship provided him with a rich influx of musical entertainment. In addition to the visits of well-known musicians at her musical evenings, Madam Brillon, herself, was an accomplished keyboard instrumentalist and composer praised by J.C. Bach and Boccherini, although her public acknowledgement was only propelled by the Franklin connection. Many of her compositions survived and some of her works uniquely feature harpsichord and piano at the same time.

It is not unusual for a music piece to initiate a sequence of descendant compositions based on the original work. In the case of Franklin’s quartet, such editions, arrangements and adaptations were likely caused by the historical value of his music rather than its musical virtues. Thus, Kaup lists the edition by Kirkpatrick published in 1958 following the original Van’s 1946 version. Also, in 1987, the arrangement by Vidulich and, most recently, the arrangement by Sarch have appeared as well. In 1963 American composer Alan Shulman wrote the Ben Franklin Suite for string orchestra based on the themes from the original composition. Finally, due to the unusual scordatura technique throughout the quartet, it was featured as one of the major examples in a treatise on string sound production from a pedagogical standpoint. Considering still the very short “published” life of Franklin’s Quartet, it is only for us to guess how many musicians are yet to be inspired by the creative wit of one of our most decorated statesmen, Benjamin Franklin.

Bibliography:

- Baird, J. & Mauger, E. A. (2006). “B Franklin: A Musical Life – Our Founding Father Was Also a Musical Maven.” Early Music America, 12 (1), 26-29, 36, 54-55.

- Cumming, R. (1967). “Francis Hopkinson: America’s First Composer.” Music Journal, 25 (3), p. 62.

- Franklin, B. (2010). Autobiography & Selected Writings. American Liberty Press, LLC. Ed. Berges,S.

- Franklin, B. String Quartet. Paris: O. Lieutier, ed. Guilliame de Van, 1946

- Franklin, B. String Quartet. New York: (unknown press), ed. J. Kirkpatrick, 1958.

- Franklin, B. String Quartet. San Diego: Nick Stamon Press, ed. M. Vidulich, 1987.

- Franklin, B. String Quartet. Boca Raton: Ludwig Music Publishing Co., arr. K. Sarch, 2008.

- Grenander, M. E. (1972). “Benjamin Franklin’s String Quartet.” Early American Literature, 7, (2), pp. 183-186. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25070569.

- Grenander, M. E. (1975). “Reflections on the String Quartet(s) Attributed to Franklin.” American Quarterly, 27, (1), pp. 73-87. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2711896.

- Gustafson, B. (1987). “The Music of Madame Brillon: A Unified Manuscript Collection from Benjamin Franklin’s Circle.” Notes, Second Series, 43, (3), pp. 522-543. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/898197.

- http://www.historycarper.com/resources/twobf3/letter3.htm.

- 12. Kaup, G. (2008). A survey and bibliography of chamber music appropriate for student string ensembles with three or more violins. The Florida State University, 3348502.

- Leonard, T. C. (1999). “Recovering ‘Wretched Stuff’ and the Franklins’ Synergy.” The New England Quarterly, 72 (3), pp. 444-455. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/366891.

- Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, post 12 May 1780 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/

- Levenberg, J. (2008). “Many Viewpoints for Many Sounding Points: Approaching Francklin’s Quartet.” American String Teacher, 58, (2), pp.40-44.

- Shulman, A. (1963). Ben Franklin Suite. Edward B. Marks Music Company.

- Marrocco, W. T. (1972). “The String Quartet Attributed to Benjamin Franklin.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 116, (6), pp. 477-485. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/985761.

- Meymandi, A. (2011). “Thomas Jefferson Loved Music.” Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 8, (7 ), pp. 54-55.

- Stolba, K. M. (1980). “Evidence for Quartets by John Antes, American-Born Moravian Composer.” Journal of the American Musicological Society, 33, (3), pp.565-574. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/831306.

Footnotes:

[1] Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, post 12 May 1780 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/

[2] For example, the poem opens up with the following strophe:

“Will you hear of a bloody Battle,

Lately fought upon the Seas,

It will make your Ears to rattle,

And your Admiration cease…”

The full text is available from Leonard (1999).

3 In fact, Leonard indicates the existence of an even earlier Franklin’s song “The Lighthouse Tragedy” based on the story of Captain Worthilake and his family’s drowning in the Boston Harbor in 1718, the text of which, as it is mentioned by Franklin in his Autobiography, was published by his brother James (p.444).

[4] The full text of this letter is available at http://www.historycarper.com/resources/twobf3/letter3.htm.

[5] Franklin’s name appears in the manuscript, as Francklin was a common French spelling in the 18th century (Grenander, 1975).

[6] Thus, Marrocco refers to a review in Allgemeine Literatur Zeitung in 1799, in which the critic wishes for the Quartet to became Ferrardini’s “last work” (1972, p. 485).

Leave a Comment: